/Book Review | Reading Time: 26 minutes

On the Uses and Disadvantages of

Exile and Diaspora for Iranian Studies*

Arash Davari | June, 2025

In the introduction to a field-defining 2011 special issue about Iranian Diaspora Studies, Babak Elahi and Persis Karim register a shift from descriptions of Iranian life outside of Iran as ‘exile’ to ‘diaspora.’ ‘Exile’ was the stock phrase used during the 1980s when large waves of expatriates settled abroad without tangible prospects for returning to Iran. As they created new patterns of life and adopted the rhythms of hosts in the United States, Canada, Europe, Asia and Australia, scholars turned their attention to consider “what it is Iranians are and experience as a result of having left Iran.” That is, where the term ‘exile’ presumed lingering nostalgic attachments to an idyllic vision of Iran, studies of ‘diaspora’ took as their object of analysis a population settled into identities as “American and European ethnics,” a population that relinquished visions of returning home without relinquishing a “link to the past.”[1]

Elahi and Karim craft their assessment in conversation with Hamid Naficy’s influential 1993 study, The Making of Exile Culture: Iranian Television Production in Los Angeles, where Naficy “seems to deploy the term ‘people in diaspora’ in contradistinction to ‘exile,’ in that exiles primarily orient themselves to the homeland while ‘people in diaspora’ relate primarily ‘with various compatriot communities outside the homeland.’”[2] The observation prefigures literary anthologies that situate “Iran and Iranian in the continuum of more global diasporic consciousness.”[3]

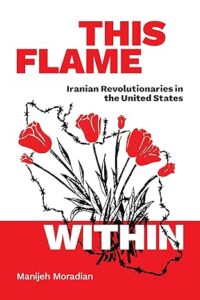

It also bears resonances to political developments, elaborated by Manijeh Moradian in her 2022 monograph This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States. Following Elahi and Karim, Moradian adopts an “intersectional approach” to “Iranian Diaspora Studies” to draw out possibilities for political solidarity between Iranian Americans and other global diasporic communities as well as with Iranians in Iran. The shift from ‘exile’ to ‘diaspora’ makes possible intellectual reflection about, and political activism oriented around, solidarity. To stand or act in solidarity requires some measure of stability in who I am apart from my relation to you.

Is there a more constitutive relationship between Iranians life abroad and Iranians living in Iran? How, if at all, do advances in Iranian Diaspora Studies inform the study of Iran? What, if anything, can the field of Iranian Studies learn from Iranian Diaspora Studies? The following essay broaches these questions through Moradian’s book and a 2009 memoir by Said Sayrafiezadeh. From among the burgeoning field of Iranian Diaspora Studies and literature, these texts stand out. Sayrafiezadeh’s book is one of the first memoirs penned and published in English by the child of leftist revolutionaries raised in the United States, while Moradian’s is among the first academic studies to theorize an Iranian leftist diaspora.

The specific circumstances faced by Iranian revolutionaries in the United States compels us to reassess prevalent definitions of ‘exile’ and, by extension, the distinction between ‘exile’ and ‘diaspora’ constitutive to the field of Iranian Diaspora Studies, or so I would like to suggest. Scholars of Iranian Diaspora Studies have rightly dispelled exilic myths and nostalgic attachments to an imaginary homeland through an assumed separation between Iranian life abroad and Iranian life in Iran. Lessons from the Iranian Left call for a renewed understanding of exile as a point of departure for critique. The course of recent history attests to the merits of this view for Iranian Studies.

Bringing Exile Back In

Hamid Naficy understands exile in a manner inclusive of Iranian life across differences in ideology, religion, ethnicity, gender, and class.

“Exile is a process of becoming, involving separation from home, a period of liminality and in-betweenness that can be temporary or permanent, and finally incorporation into the dominant host country. Although separation begins with departure from the homeland, the imprint, the influence, of home continues well into the remaining phases and shapes them. Liminality and incorporation involve ambivalences, resistances, slippages, dissimulations, doubling, and even subversions of the cultural codes of both the home and host societies. The end result is not unified or stable; it is an evolving syncretic and hybrid exile culture.”[4]

In Naficy’s estimation, exile is a state of flux moving toward partial incorporation. He appreciates “exilic cosmopolitanism” for the fundamental doubt it fosters with regard to “the self, reality, home, traditions—in short, doubt about absolutes, ideologies, and taken-for-granted values of one’s home or host societies.”[5] And yet, while Naficy acknowledges the lingering effects of displacement—a “period of liminality and in-betweenness that can be temporary or permanent”—and an end result that “is not unified or stable,” he depicts exile as a “process of becoming” that settles into a syncretic identity. Iranian exiles become Iranian Americans.[6] Building on Naficy’s framework, Iranian Diaspora Studies examines the shape syncretic identity can take in all its variety, as exiles settle into their host countries and newfound homes.

Naficy’s notion of exile resembles another influential account penned by Edward Said, for whom exile describes “the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home,” transformed into “a potent, even enriching, motif of modern culture.”[7] For all the pain and suffering it creates—and the measure of pain is considerable in Said’s view—the condition also fosters a unique perspective on worldly affairs.

“Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that—to borrow a phrase from music—is contrapuntal. For an exile, habits of life, expression, or activity in the new environment inevitably occur against the memory of these things in another environment. Thus both the new and the old environments are vivid, actual, occurring together contrapuntally.”[8]

With reference to the contrapuntal, Said describes the perspective afforded by exile as the retention of two ways of life without reconciliation in one. Naficy, by contrast, favors syncretism: the fusion of two dissonant elements into a partial whole. This difference follows from another of consequence to Iranian leftists living abroad. For Naficy, exile

“…refers to individuals or groups who voluntarily or involuntarily have relocated outside their original habitus. On the one hand, they refuse to become totally assimilated into the host society; on the other hand, they do not return to their homeland—while they continue to keep aflame a burning desire for return. In the meantime, they construct an imaginary nation both of the homeland and of their own presence in exile.”[9]

So construed, exile includes both voluntary or involuntary relocation. It follows that the insistence to “keep aflame a burning desire for return” is voluntary or involuntary as well. Indeed, the transition from ‘exile’ to ‘diaspora’ depends on one’s volition, on the willingness to extinguish this flame, at which point diaspora casts its own broad ambit, including Iranians from all walks of life. Said’s description of exile, however, indicates an involuntary condition:

“Although it is true that anyone prevented from returning home is an exile, some distinctions can be made among exiles, refugees, expatriates, and emigres. Exile originated in the age-old practice of banishment. Once banished, the exile lives an anomalous and miserable life, with the stigma of being an outsider.”[10]

The enduring “stigma of being an outsider”—the fate of an “anomalous and miserable life” that follows from banishment—precludes even the partial resolution Naficy attributes to syncretic identity. In Said’s reading, exile offers critical insight on account of unmitigated pain, suffering, and loss.

Said’s concept of exile more closely resembles the predicament of the Iranian Left abroad, the subject of Moradian and Sayrafiezadeh’s books, which more closely resembles an involuntary condition of banishment and anomaly. Iranian leftists lost the battle for postrevolutionary state power and found themselves banished from the homeland to which they dedicated their lives, either as internal exiles prevented from traveling abroad or as external exiles who could not return home without risk until after the Cold War. Unlike Iranian royalists and other champions of the ancien regime, who found ideological affinity with their environs in Europe and the United States, Iranian leftists secured relative safety and partial stability at the cost of denying themselves: staunch anti-imperialists, their new abode was now in the imperial core.

More judicious engagement with the circumstances of the Iranian Left abroad thus reveals the limits of Iranian Diaspora Studies and the merits of Said’s approach. And, on this accord, we may draw from the experiences of Iranians abroad to develop conceptual lessons of use to the study of Iran.

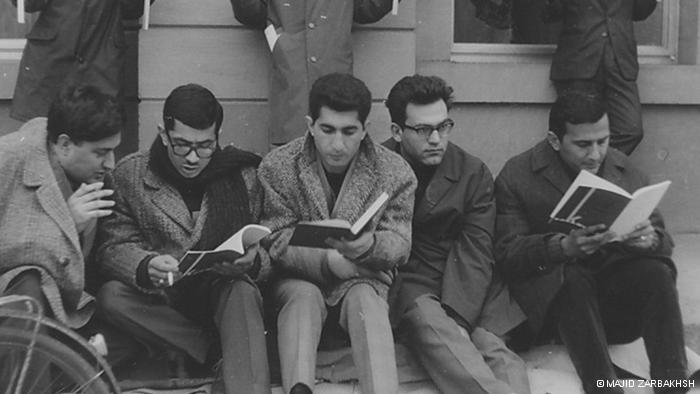

Remembering Revolution

Moradian published a memoir essay in 2009 under the penname Nasrabadi in which she describes her relationship with her father. The essay appeared in Callaloo—a journal dedicated to “matters pertinent to African American and African Diaspora Studies worldwide.”[11] It was a fitting venue given the elder Moradian’s years of service as a professor of architecture at Howard University, an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) where during the 1970s he sympathized with and supported student activists in the Iranian Students Association (ISA).[12] The venue is all the more fitting given the younger Moradian’s recent monograph which, among many groundbreaking contributions, demonstrates “affects of solidarity” between Iranian and Black American student activists in the 1970s.

The essay recalls the longing she felt for her father’s affection as he turned away from his nuclear family, distracted by the dizzying events of the 1979 revolution in Iran, and then inward as political events eluded his dreams and aspirations. A three-year-old Moradian watches her father leave for an ecstatic visit to his home country. Basking in the fervor of revolutionary possibilities, he implores his American Jewish wife to join him with their two small children. The mother refuses, compelling the father to return to the United States, where a backlash to the seizure of the US embassy in Tehran makes life inhospitable. The elder Moradian tells his family the decision to live in exile was solely for their sake. His air is melancholic and detached, only interrupted by eccentric forays in his children’s upbringing. If he cannot participate in the reconstruction of Iranian society, he decides to raise a pair of revolutionaries from afar. The younger Moradian recounts with vivid prose her earnest efforts to fill the gap in the elder Moradian’s heart, to recover the father she once had by performing as best she could his quasi-Maoist training regimen. When she falls short or delivers some perceived slight, her father turns on her, at times resorting to physical violence.

Moradian’s essay bears resemblance to Sayrafiezadeh’s When Skateboards Will Be Free, another touching, at-times humorous, and also painful memoir published in 2009.[13] Sayrafiezadeh recounts a similarly fraught relationship with an absent father—a man who never seemed ready to accept the loss associated with the 1979 revolution and who abandoned his familial responsibilities in stubborn pursuit of communist liberation as it faded from view. Mahmoud Sayrafiezadeh was also a professor, of mathematics, and at one time a member of the Society for Iranian Studies (SIS), the precursor to today’s Association for Iranian Studies.[14] He was a prominent figure in the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), established the first Trotskyist party in post-revolutionary Iran, and ran a negligible campaign to become president of the Islamic Republic in 1980. He would later staff the booth for Pathfinder Press at Iran’s annual book fair. All the while, his son endured a difficult upbringing in the care of a single mother who struggled to provide for him while maintaining her commitments to the Party and the cause. An American Jewish woman with a privileged upbringing, she refused to pursue her dreams and individual pleasures (or even the semblance of an orderly life) despite access to considerable educational and financial resources, all in a vain attempt to identify with the working class.

When Skateboards Will Be Free delivers sharp criticism of leftist organizational politics, drawing a portrait of people hopelessly out of touch with reality. Sayrafiezadeh reserves special ire for the selfishness and hypocrisy of his father, a man who proclaimed to dedicate his life to fighting for a just world while neglecting to treat his wife and his child with dignity. Readers are invited to reject the grand prescriptions and empty gestures of ideological purity espoused by Sayrafiezadeh’s parents and instead celebrate the virtues of a simple and honest living embodied by his American in-laws. One cannot help but empathize given the absurd challenges Sayrafiezadeh faced on account of the Party’s mandates. The mere act of publishing an intimate account breaks ground rules that prohibit against airing “dirty laundry.” Little surprise then that When Skateboards Will Be Free severs Sayrafiezadeh’s already strained relationship with his father, and the Party, for good.

Like Sayrafiezadeh, Moradian harbors resentment, but she directs the sentiment to the pursuit of liberation, mixing bitter memories with reverence for the promise of the Left. Hers is an upbringing in diaspora marked by continued engagement with Iranian politics, including a trip to Iran—a reflection perhaps of her relationship with her father who, despite his emotional absence, remained physically present in her life. Moradian’s memoir thus ends with a different sort of longing.

“Now I can’t help but wonder, if my father could’ve grieved openly for the death of the revolution, what kind of a man he might have been. I imagine a support group for Iranian leftists like him, men and women who’d spent years organizing on their campuses in America and who’d thought, at first, that the revolution was a step forward on the path to socialism. A place of shelter from suspicion, where he wouldn’t have to be defensive, where he could sit with his former comrades and show how broken he was as his country was torn apart by bombs made in the USA. But of course, there was no such place.

Both the Iranian and the American governments would write the secular, democratic chapters out of official histories of the revolution and sum everything up with the word Islamic.

And I would forget for almost thirty years that I’d sung ballads in Persian, that I’d taken enemy hills and tackled my father on the Chinese grasslands of our backyard. I would forget all about the days before the magic had faded, when we’d tried our best to hold on to something good.”[15]

Moradian’s 2022 monograph is one such place, a shelter for people mired in the disenchantment that follows revolution. This Flame Within reconstructs the story of the ISA, the North American affiliate of the Confederation of Iranian Students, National Union (CISNU). Moradian takes the memories of Iranian student activists who adopted a nationalist, radical leftist, and secular brand of politics, united by a shared desire to precipitate revolution in Iran, and recasts their efforts as a diasporic vision for Iranian politics of enduring relevance today.

Face-to-face with the event they spent years trying to ignite, members of the ISA were surprised to find themselves shunned from all sides—by the Islamic Republic for the secular orientation of their revolutionary politics, by fellow Iranians in America for having been revolutionaries in the first place, and by the hostility of the American populace at large. This Flame Within responds to the second of these critics, the “mainstream Iranian diaspora” comprised of emigres who arrived on American shores after 1979 harboring near-fascist nostalgia for the Pahlavi state. They set the tenor for political discourse, blaming Iran’s demise on leftist miscalculations with equal vigor as racist tropes about Islam. Their version of public memory made it taboo to recall with fondness revolutionary pasts, relegating to whispers the feeling of ecstasy ISA members like Moradian’s father experienced on their returns to Iran in the early months of the post-revolutionary order. Indeed, the mainstream diaspora has been so constitutionally averse to the prospect they opted to stage demonstrations for “regime change” during 2022’s “Women, Life, Freedom” movement, avoiding the word revolution in blatant defiance of activists on the ground who insisted theirs was a revolutionary cause.[16]

Moradian’s book is both a rejoinder and an attempt to thread an almost impossible needle. She rebukes the endorsement of the “progressive clergy” adopted by most ISA members, and yet she embraces the visions they espoused as a template for present-day politics. In other words, she sketches a posture of dual opposition to the Islamic Republic and the US, anti-dictatorship and anti-imperialism. This Flame Within ingeniously reclaims nostalgia to make the case. It refuses descriptions of melancholic attachment as pathology—a despondent longing for what could have been, cured if only we could relinquish the past and accept present-day realities for what they are. The book is equally averse to melancholia as disavowal—out-of-touch images of grandeur about the Pahlavi monarchy and pre-Islamic Iran meant to temper the harshness of life in exile. Instead, Moradian offers a concept of “resistant nostalgia” according to which melancholy serves as a reservoir for militancy against the odds. Resistant nostalgia affirms the past despite the pain it brought ISA members. When yesteryear’s leftists nurture “this flame within” through hidden melancholic attachments, they maintain a tradition of resistance for later generations poised to redefine it in response to emergent historical circumstances of their own accord. Moradian performs the relay, bringing back in “the secular, democratic chapters” left “out of official histories,” giving her father the recognition he lacked, mitigating the hurt that led him to hurt her.

Her book ranks among those rare scholarly monographs that address the wounds borne by people for whom politics is an intimate affair.[17] It should be read alongside Moradian’s poignant 2009 memoir and the recollection of her father’s despair as an ambitious and inspiring attempt to break the cycles of unacknowledged pain that afflict former revolutionaries and their children in the wake of mass upheaval. Phrased differently, This Flame Within diagnoses the loss Sayrafiezadeh’s father refused to acknowledge and, by extension, his refusal to properly acknowledge his son’s life. As Amy Malek notes in an astute review focused on method, Moradian constructs a “living archive of memory” and, so doing, brings that archive to life for the reader, describing with care “the gestures, facial expressions, pauses, and even flat affects she observed.”[18]

Moradian’s study draws on interviews with a representative range of figures active in the ISA, some of whom held key leadership positions. She adds to these interviews with activists from non-Iranian organizations whose lives were bound with the ISA, including one woman who went to Iran after 1979 where she was detained. These stories alone make for novel contributions to a history previously focused on Iranian students and American policy.[19] Moradian goes further, pairing the interviews with careful analysis of publicity documents, ephemera, and literature produced by the ISA and adjacent groups from the Black American, Arab American, and Ethiopian student movements as well as the anti-war movement against the American war in Vietnam.

To navigate this vast and unwieldy archive, This Flame Within invokes Queer Studies and Affect Theory. It is a diasporic choice to interpret Iran and Iranians with theoretical traditions rooted in the European and North American academy. Barring a few exceptions, Iranian Studies has failed to engage these particular traditions, a glaring oversight made evident when recent Iranian social movements put the ideas to use and experimented with their forms.[20] In this sense, among others, Moradian builds a bridge between Iranian Studies and Iranian Diaspora Studies.[21] Likewise, she builds a bridge between past and present, drawing from the history of the ISA to develop a framework for contemporary analysis and critique. Alongside “melancholic attachments as resistant nostalgia,” the book’s core theoretical constructs include: a “methodology of possibility” (roads not taken by past political movements that may prove useful for present-day concerns); “revolutionary affects” (the sentiments experienced in past trauma as impetus for present-day activism and the feelings of belonging that kept students engaged in shared struggle); and, finally, “affects of solidarity” (sentiments held in common with other racial and ethnic groups in America, forging a model of solidarity beyond identity politics).[22]

Any attempt to recover forgotten pasts is bound to create its own occlusions. Take for example one of Moradian’s central interventions, “affects of solidarity,” which emerges through careful analysis of ISA’s English language publications. Her groundbreaking research on this front, among others, prompted Afshin Matin-asgari to recognize This Flame Within as a valuable addition to his 2001 book, Iranian Student Opposition to the Shah, the most comprehensive history of the CISNU and the ISA to-date.[23] And yet, what This Flame Within gains by focusing on solidarity with non-Iranians, it loses with regard to the student movement’s internal dynamics. Unlike Matin-asgari’s study, Moradian scarcely engages the immense amounts of Persian-language materials produced by the ISA where we see bitter ideological divides erode feelings of solidarity among members. Matin-asgari’s signature contribution was to show how a democratic apparatus kept activists together for a time despite pronounced ideological differences. It remains for future research to explore the “revolutionary affects” cultivated by addresses to Persian-language audiences, be it ones in Iran or other activists in America, and, further, how student activists weathered the storms of ideological dispute to maintain a shared sense of belonging among themselves while developing connections with others.[24]

Similarly, despite attention to the material qualities of affect, This Flame Within does not pay much mind to conventional class distinctions.[25] There were different political cultures within the ISA over its decades of existence, some of which mapped along class lines. If the 1960s saw members drawn from “imperial model minorities”—economically privileged students whose traumatic experiences of the 1953 coup inspired them to become revolutionaries against expectations to the contrary—the 1970s saw an influx of lower middle-class students who developed cultures of belonging through relationships of mutual care shaped by economic survival abroad. Moradian aptly describes the former. How the latter shaped “affects of solidarity” remains ripe for further exploration.

A stickier problem haunts Moradian’s attempts to vindicate the past in the present or, in more technical jargon, to combine a descriptive register with a prescriptive one. This Flame Within weaves a brilliant story about the pursuit of “gender sameness” in the ISA, an ideal that empowered women members so long as they mimicked masculine norms (Chapter 5). This analysis extends Haideh Moghissi’s observations about gender politics within the Fadaiyan Organization, deciphering similar patterns among Iranians abroad.[26] Like their Fadai peers, practices of self-cultivation left ISA members ill-equipped to stand in solidarity with Iranian women on March 8, 1979, when thousands protested the state’s attempt to gender citizenship and exert control over women’s bodies through enforced hijab. Against the demure, veiled presentation of women’s bodies expected by an emergent Islamic Republic—whose decrees paralleled sartorial choices adopted by members of the ISA, Maoists in particular—protestors asserted women’s capacity to embody femininity. Consistent with a “methodology of possibility,” Moradian considers roads not taken, posing an alternative to the choice between gender equality as Western imperialism and anti-imperialism as support for a patriarchal state (Chapter 6).

In other words, Moradian argues for an anti-imperialist and anti-authoritarian leftist politics that would exist apart from both Islamophobia and apologia for the Islamic Republic. Here, she builds on woman-of-color and Third World feminist approaches to the “dirty laundry” debate. Rather than concede the idea that public expressions of internal critique endanger “oppressed and targeted groups” by giving an excuse to those who “do us harm,” This Flame Within advances an “intersectional Iranian diaspora studies framework.” Opposition to “gender and sexual oppression” thus makes “movements against racism, economic exploitation, and imperialism…stronger and more effective” (19-20).

For all its insight, combining descriptive and prescriptive registers can produce uneven readings of history. These, in turn, raise unanswered questions about the prescriptions on offer and relatedly Moradian’s methodology. It was commonplace in 1979 to draw distinctions between “feminist” activism and “political” activism.[27] Moradian’s prescriptive argument rebukes this divide, citing the ISA’s absence from the March 8 protests as evidence of its misguided nature, and yet her descriptive account of what transpired, the basis on which she advances judgment, is not entirely accurate. This Flame Within repeats a history that portrays the famed demonstration on March 8 against compulsory hijab as interconnected with “six days of mass marches and sit-ins,” including the March 10 “mass sit-in outside the Ministry of Justice” (227).[28] This narrative glosses over important points of potential difference, consequential for Moradian’s argument. Notably, the terms of the March 10 sit-in allowed partisans to assume “gender sameness” while still taking part in the women’s uprising.

The March 10 sit-in was led by the Association of Barristers [Kanun-e Vokala], a member of which, Parivash Khajehnouri, read a declaration from an organization named ‘Women in the Court of Justice’ [Zanan dar Dadgostari]. The statement reiterated calls for women to make their own sartorial choices, echoing the March 8 uprising, but also it demanded the preservation of “women’s present employment.”[29] Indeed, despite all the attention given debates about hijab and bodily autonomy today, for many the first alarms about gender equality in post-revolutionary Iran were raised by rumors about the removal of women judges and the prohibition of women from professions requiring the exercise of judgment.[30] In this light, one can imagine people who participated in the sit-in on March 10 but not the demonstration on March 8, who continued to adhere to the principle of “gender sameness,” who understood women’s equality to mean the capacity to exercise a form of disembodied judgment, and who prioritized rationality over affect, “politics” over “feminism.” How might these alternative histories fit in Moradian’s story about “revolutionary affects”? Are they out of line with contemporary struggles against imperialism and dictatorship? Is advocacy for rational judgment through “gender sameness” the wrong sort of “melancholic attachment”? If not, where does that leave Moradian’s prescriptions for contemporary political critique?

Moradian’s prescriptive arguments about Islam obscure descriptive accuracy in a different way. This Flame Within is entirely correct to note a lack of rapport between members of the ISA and Islamists, who comprised a separate minority of student activists in the United States. Moradian ably recovers a radical secular tradition, one that exists beyond the post-9/11 imperative that anti-imperialism should embrace Islamism to counter Islamophobia. And she does not hold punches along the way, noting the ISA’s mistaken approach when it endorsed the “progressive clergy.” The argument works extremely well in response to the “mainstream Iranian diaspora,” whose Islamophobia understands any form of Islamism as noxious and who seek to undermine the Left by pegging it with the Islamic Republic. But the effort to counter an Islamophobic mainstream can overlook enduring Islamophobia within the Iranian Left.[31] Further, it disregards an empirical reality from the past half century: the relative effectiveness of Islamism as a rallying point for another kind of anti-imperialist politics, modular across various groups and struggles in the Middle East. The latter stands as a material fact, one that leftists must reckon with if they wish to aspire to universalism (a defining feature of the Left).

Let us consider the point through Moradian’s insights. This Flame Within demonstrates the experimentation pursued by a pioneering generation of radical and secular Iranians living abroad. They took courageous steps by extracting themselves from past traditions while inventing ones of their own whole cloth, an endeavor that set them in search of political belonging.[32] It is not clear from Moradian’s book, or from the history of the ISA, whether leftist opposition to the Islamic Republic must foreclose similar experimentation with Islamism or, at a more basic level, why opposition to dictatorship must entail revolutionary opposition to the Islamic Republic. Given the orientation of Iranian leftists who assume opposition to the Islamic Republic prima facie, it is uncertain whether an Iranian Left would survive the effort.[33] And yet still, we may hold the question open. We must if we wish to recall the form and spirit of the past, rather than solely its content.

Here, we see a misalignment between the content of Moradian’s prescriptive statements and the form of her masterly engagement with a “living archive of memory,” which, as I understand, invites a continued exercise of judgment. If we read Moradian and her interlocutors as mobilizing affect in cynical fashion toward a specific political agenda, we would arrive at the conclusion that enduring attachments to a leftist cause are at odds with the unscripted possibilities implied by judgment. To end our analysis here would vindicate Sayrafiezadeh. He was right to reject his parents’ leftist past and to harbor suspicion of a penchant among revolutionaries for conscripting others into their agendas, empirical fact and divergent desire be damned.

I am more convinced by Moradian’s methodological approach, or at least the possibilities contained therein. She invites us to stretch our imaginations, to take an even further leap of faith. It is possible, I hear her saying, to excavate history while holding to a political telos. In fact, we should. For an archive to live, the author who invokes memory must stake her position, not retreat into the righteous comforts of personal experience and injury. Moradian is correct to advance her own prescription and political vision regardless of whether the reader thinks the substance of her position is ‘correct.’ The gesture alone links past to present in unforeseeable ways. But we should expect the gesture to be just that. It should give the reader an opportunity to exercise their own judgment and bring an archive to life in their own right. Those of us who read and write about revolution would do well to take heed, maintaining a distinction between our “resistant nostalgia” and the “resistant nostalgia” of the erstwhile revolutionaries whose lives and actions fill the books and the memories we carry. Moradian’s book gives us the gift of a language to ask these questions, a way to approach the living archives within our communities.[34] It is, for this reason, an enormous contribution to the study of Iran. To appreciate the scope of that contribution, we may venture beyond the parts of Moradian’s study tethered to Iranian Diaspora Studies and recall an exilic perspective.

On the Uses and Disadvantages of Exile and Diaspora for Iranian Studies

Among the Iranian students who attended American universities before the 1979 revolution, a select few focused on academic research in the social sciences and humanities, and formed the SIS in 1967, a precursor to the Association for Iranian Studies (AIS).[35] Political cadres from the ISA took the young graduate students to task for their passive, seeming complicit silence in the face of the Pahlavi state’s human rights violations. We may imagine early members opting to keep criticism of the state to themselves out of fear, shrewd calculation, and principled resistance, receiving in exchange tacit permission to travel to and from Iran unhindered.

Iranian Studies scholarship has largely ignored the ISA in the decades since, adhering to an area studies model that values events in the territorial nation-state of Iran as the correct purview of Iranian Studies. The youthful naïveté and ideological blinders of the ISA, exposed by the outcome of the revolution, made it easy to forget the group. Iranian Diaspora Studies struggled to gain footing in like fashion. Works by scholars trained in American Studies, Gender and Women Studies, and Ethnic Studies were regarded as objects of marginal interest at best. At worst, they were not up to par with the standards of empirical analysis and its attendant skills: language mastery, familiarity with Iran, and immediate presence. These sentiments gained momentum along with what they sought to dispel—the fanciful nostalgia and ideological battles around the 1979 revolution prevalent in popular debate. Each in its own way projected an image of “Iran” uncontaminated by what happened beyond its borders.

Barring a few notable exceptions, early exponents of Iranian Studies could not pursue fieldwork in post-revolutionary Iran. Post-revolutionary power struggles, the cultural revolution in Iranian universities, and an eight-year war with Iraq rendered academic exchange difficult. It would take a new generation of scholars to deliver rigorous empirical studies of the Islamic Republic. As the state consolidated and postwar Iranian society gained stability during the 1990s and 2000s, scholarship predicated on direct contact with Iranians living in Iran gained epistemic priority over the theoretical pronouncements by expatriate Iranians, dismissed for repeating empty slogans from a bygone era.

Turns in knowledge production toward lived experience corresponded with shifts in Iranian politics away from fanciful revolutionary ideals. The decades prior and immediately following the 1979 revolution in Iran were dominated by utopian blueprints, from the Pahlavi government’s modernization schemes to iterations of Marxism in opposition to the state and the Islamic ideology that displaced it. With the end of the Cold War and the concomitant demise of “dreamworlds,”[36] a pragmatic ethos prevailed in the Iranian public sphere. It coursed through the halls of power: the revised constitution of 1989 emphasized political authority over religious jurisprudence and granted an “expediency” council final say over the administrative state. Meanwhile, Islamic leftists driven out of parliament reconstituted themselves as a reform movement, united by their rejection of earlier utopian ideals.[37] The tables turned yet again as Iran’s Reform movement stalled. The entrenchment of the Islamic Republic, which had forged infrastructure for rigorous study of lived experience in Iran, now became a point of animus and frustration. During the 2010s, a newer generation of activists in Iran cited the authority of lived experience in polemics against the scholars who first championed it.

Iranian dissidents made pragmatic use of the Iranian diaspora to navigate treacherous political terrain in Iran. When and where it served their tactical interests, one could champion certain figures over others. Take for instance longstanding affinities between Reformists and the National Iranian American Council (NIAC), or allegiances between more radical activists and opposition figures like Reza Pahlavi, Masih Alinejad, and Hamed Esmailioun. Conversely, dissidents used the diaspora as a foil to articulate criticism of the state. This may explain pronounced expressions of ire directed against NIAC during the 2022 uprising, when Persian-language speakers transformed the organization’s name from an innocuous acronym into a pejorative adjective. The phrase Niaci came to signal complicity with the state’s most repressive acts, shorthand for how not to be diasporic—or, how not to act in the interest of the Iranian state. In 2022, popular denunciations of Niacis caught “experts and professionals” in its net regardless of ideological affiliation.[38]

The Iranian Left fit oddly in these polemics. On the one hand, significant portions had adopted muted criticism of the Islamic Republic in its formative years to pursue anti-imperialist objectives. On the other, the Left suffered harsh repression, culminating in banishment and exile. On the one hand, significant portions of the Iranian Left had called perceived opponents Savaki, a reference to the Pahlavi state’s intelligence apparatus turned adjective and an obvious precursor to twenty-first century term Niaci. And members of the ISA had targeted their studious peers, much akin to the attacks against “experts and professionals” levied by some Women, Life, Freedom activists. On the other, many contemporary activists derided the historic Left and called those who pursued any inkling of an anti-imperialist agenda Niaci.

Moradian summarizes the Iranian Left’s predicament succinctly. Settling into life in the United States without a promise to return compelled a “leftist diasporic mandate to only criticize ‘our own government,’ meaning the US government…driven by the legitimate fear that saying anything negative about Iranian society can and will be used as a justification for sanctions, war, and US-sponsored ‘regime change’” (19). Moradian finds an alternative in the memories and archives of Iranian student activists from the 1960s and 1970s a “multifaceted and multi-sited critique of imperialism and dictatorship, and its consistent practice of making connections between oppressive conditions in the US and in Iran” (21). Thus, This Flame Within proposes a politics of solidarity based on an Iranian diaspora distinct from Iranian exile. Rather than propose a return to Iran—an impossible feat and a persistent reminder of defeat—the Iranian leftist diaspora may act in relation to other diasporic communities mobilized against patriarchy and US empire. Or: a “people in diaspora” (per Naficy), leftist Iranians may see themselves “in the continuum of more global diasporic consciousness” (per Elahi and Karim) and thus foster “affects of solidarity” with similarly banished communities in the United States (per Moradian).

To make this claim, Moradian invokes notions of diaspora even as she describes the Iranian left in terms akin to Said’s notion of exile—a condition of irresolute unbelonging and anomaly, embattled from all sides. The shift from ‘exile’ to ‘diaspora’ in Iranian Diaspora Studies parallels the shift from utopianism to realism in Iranian politics. Diaspora describes Iranians abroad who relinquish utopias—fanciful images of a past home to which they belonged and to which they intend to return. Exiles become diasporic when they came to accept reality and its limitations, tempering revolutionary (and counterrevolutionary) visions with their real-life consequences. It would be fair to ask whether we can adjudicate revolutionary prospects from an Iranian Diaspora Studies perspective.

There are compelling empirical reasons to pursue Iranian Diaspora Studies today. The many crises that befall life in Iran today continue to spur emigration, further projecting Iranian lived experience outside the parameters of the territorial nation-state and traditional area study. As activists entertain transformations of revolutionary scale, the musings of exiles who once yearned for fundamental social change no longer seem out-of-reach.

We should temper these longings with Said’s vision of exile, an idea void of expectation for deliverance, suited to historical description of lived experience among the Iranian left. A short three years after the Woman, Life, Freedom led many abroad to believe the demise of the Islamic Republic was near, Iranian state and society endured a twelve-day war of aggression by American and Israeli forces, after which resurgent nationalist sentiment displaced universalist pretensions toward feminist solidarity.

An exilic perspective thrives in the interstices of a discomfiting choice between transnational ideals of grassroots social movements and pragmatic defenses of developmentalist states. It teaches us to relinquish modes of condemnation rooted in claims to belonging, passed on from previous generations to contemporary activists. And it calls for fortitude to dwell in uncertainty. The pain of exile is grounds for insight, and a far cry from the certitude that permits condemnation. To reshape Iranian Studies from Iranian exile is to decipher the limits of lived experience as an epistemological referent and to refrain from imposing political programs on scholarly inquiry, if only to discover unexpected possibilities beyond where we think we belong.

Endnotes

* Author’s Note: This is an expanded version of a review essay originally published in the journal Iranian Studies, volume 57, issue 4

- Babak Elahi and Persis Karim, “Introduction: Iranian Diaspora,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 31, no. 2 (2011): 382. ↑

- Elahi and Karim, “Iranian Diaspora Studies,” 383. ↑

- Elahi and Karim, “Iranian Diaspora Studies,” 383-384. ↑

- Hamid Naficy, The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian Television in Los Angeles (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), xvi. ↑

- Naficy, The Making of Exile Cultures, 9. ↑

- Naficy, The Making of Exile Cultures, 6-16, 188-195. ↑

- Edward Said, “Reflections on Exile” in in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 173. ↑

- Said, “Reflections on Exile,” 186. ↑

- Naficy, The Making of Exile Cultures, 16. ↑

- Said, “Reflections on Exile,” 181. ↑

- See https://www.callalooliteraryjournal.com/about-callaloo. ↑

- See “In Conversation: Manijeh Moradian with Golnar Adili,” The Brooklyn Rail (February 2023): https://brooklynrail.org/2023/02/books/Manijeh-Moradian-in-conversation-with-Golnar-Adili/ . ↑

- I am grateful to Alexander Jabbari for bringing the resonances between these books to my attention. ↑

- The Society for Iranian Studies, S.I.S. Newsletter 6, no. 1 (January 1974): 15. ↑

- Manijeh Nasrabadi, “A Far Corner of the Revolution,” Callaloo 32, no. 4 (2009): 1207. ↑

- “Jin Jiyan Azadî as in Free Palestine,” Jadaliyya (November 23, 2023): https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/45544/Jin-Jiyan-Azadî-as-in-Free-Palestine. ↑

- Elleni Centime Zeleke published a comparable volume about the Ethiopian revolution in 2019. Zeleke’s work is distinct insofar as she develops a theoretical and methodological approach through conversation with vernacular traditions from Ethiopia. She calls this approach “theory as memoir.” See Elleni Centime Zeleke, Ethiopia in Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production, 1964-2016 (Leiden: Brill, 2020). ↑

- Amy Malek, “Reperiodizing, Reclassifying, and Reframing the Iranian American Diaspora in This Flame Within,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 44, no. 1 (2024): 181. ↑

- See, e.g., Afshin Matin-asgari, Iranian Student Opposition to the Shah (Washington, D.C.: Mazda Publishers, 2001); Matthew Shannon, Losing Hearts and Minds: American-Iranian Relations and International Education during the Cold War (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2017). ↑

- See, e.g., L., “Figuring a Women’s Revolution: Bodies Interacting with their Images,” trans. Alireza Doostdar, Jadaliyya (October 5, 2022). ↑

- Golnar Nikpour, “On Revolutionary Possibility in the Archive of 1979,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 44, no. 1 (2024): 176–77. ↑

- Similar topics arose in philosophical writings by activists from the Ethiopian student movement, many of whom were in conversation with the ISA. For reference, see Arash Davari, “Solidarity to Fraternity,” Review of Ethiopia in Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production, 1964-2016 by Elleni Centime Zeleke, Radical Philosophy 2, no. 10 (2021): 87-91. ↑

- Afshin Matin-asgari, Review of This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States by Manijeh Moradian, Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 23, no. 1 (2023): 147-150. ↑

- Ali Nadimi’s memoir—first published in 2017 and recently translated into English—offers clues for future research. Nadimi describes relations of solidarity between student movement activists abroad and guerrillas in Iran, notably paying attention to their affective dimensions. He recounts how statements of solidarity from activists in Iran “stirred emotions and brought many participants to tears” at the fifteenth CISNU congress in Germany in January 1974. Nadimi compares reception of these internal solidarity statements with reception of solidarity statements from non-Iranian organization, “CISNU’s traditional allies” or “international organizations and liberation movements from across the globe.” He situates these affects of solidarity in relation to “the useless disputes and rash, unmeasured reactions” that fueled conflict among Iranian student activists. See ‘Ali Nadimi, “The Confederation of Iranian Students (National Union) and the Fada’i Guerrillas,” trans. Arash Davari, in Fada’i Guerrilla Praxis in Iran (1970–1979): Narratives and Reflections on Everyday Life, eds. Touraj Atabaki, Nasser Mohajer, and Siavush Randjbar-Daemi (London: I.B. Tauris, 2023), 203-215. ↑

- Abdel Razzaq Takriti, “Embodying Solidarity in the Heart of Empire,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 44, no. 1 (May 1, 2024): 185. ↑

- Haideh Moghissi, Populism and Feminism in Iran (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 115-122. The sentiment corresponded with an emphasis on ascetism within the guerrilla movement. See ibid., 131-132, 135. ↑

- See, e.g., Mahnaz Matin and Nasser Mohajer, Khizesh-e Zanan-e Iran dar Esfand-e 1357 (Koln, Germany: Nashr-e Noghteh, 1392/2013-14), 145, 152. ↑

- The narrative also appears in Moghissi, Populism and Feminism in Iran, 140; Mehrangiz Kar, Crossing the Red Line: The Struggle for Human Rights in Iran (Costa Mesa, California: Blind Owl Press, 2007), 46. ↑

- For context and a partial reprint of the original statement in Persian, see Matin and Mohajer, Khizesh-e Zanan, 71-73. For an English language translation of the statement, see Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), 245-246. The translation does not mention who read the statement on March 10, 1979. The Persian-language reprint omits article 7 regarding the preservation of women’s “present employment.” ↑

- For a personal account that demonstrates the point, see Matin and Mohajer, Khizesh-e Zanan, 144. ↑

- Arash Davari, “Like 1979 All Over Again: Resisting Left Liberalism Among Iranian Émigrés” in With Stones in Our Hands: Writings on Muslims, Racism, and Empire, eds. Sohail Daulatzai and Junaid Rana, 122-135 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018). ↑

- Like Zeleke, Moradian’s argument adds a diasporic inflection to existing scholarship about vernacular Marxism. See, e.g., Fadi A. Bardawil, Revolution and Disenchantment: Arab Marxism and the Binds of Emancipation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020). ↑

- I am grateful to Roozbeh Shirazi for bringing this point to my attention. ↑

- I am grateful to Amy Malek whose feedback helped me clarify this point. ↑

- Renamed the Association for Iranian Studies (AIS), it remains a thriving professional association united by a “non-political” identity. The phrase appears in the AIS’s bylaws as an injunction against campaign financing, a stipulation required of all NGOs registered in New York State. See https://associationforiranianstudies.org/about/ais-bylaws. It has been adopted informally as an organizational ethos to distinguish the AIS from what scions deem to be the undesirable emphasis on politics by the Islamic Republic (and, perhaps implicitly, by their counterparts in the ISA). ↑

- The phrase belongs to Susan Buck-Morss, Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West (Cambridge, M.A.: The MIT Press, 2000), x-xi. ↑

- Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, Islam and Dissent in Postrevolutionary Iran: Abdolkarim Soroush, Religious Politics and Democratic Reform (Tauris, 2008); Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, “The Divine, the People, and the Faqih: On Khomeini’s Theory of Sovereignty,” in A Critical Introduction to Khomeini, ed. Arshin Adib-Moghaddam (Cambridge University Press, 2014); Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, Revolution and Its Discontents: Political Thought and Reform in Iran (Cambridge University Press, 2019). ↑

- NIAC is a non-profit lobbying group in the United States. Since its founding in 2002, on the heels of then-president Mohammad Khatami’s calls for “a dialogue of civilization,” NIAC’s raison d’être had been to service business interests for Iranian Americans keen on pursuing entrepreneurial ventures in Iran. Its signature achievement was advocacy of a nuclear deal in 2015, promising friendly political relations with the Western world and by extension commerce befitting Iranian investors among the Islamic Republic’s oligarchic class adept at exchange with companies in the West. NIAC’s impact was marginal and largely went unnoticed until prospects for reform dimmed and social movement demands turned radical in the 2010s, calling for the decline of the regime. ↑

Comments are closed.