Organizing at Universities and Unfolding Revolution in Iran

[1]I am indebted to Farhad No’mani, Sohrab Behdad and Guiti Etemadi who accepted my invitation to be interviewed about their experiences with the NOUP in winter and spring 2023. They generously … Continue reading

Azam Khatam

Jun 15, 2024

Reading Time: 28 minutes

The 1978 Iran saw a surge in social and political activism. A multitude of initiatives emerged, all striving for ambitious goals: fostering collective action and transforming the established social order. Popular slogans of independence and freedom resonated with the ideals of both the secular left and pro-Taleghani Islamists. This common ground lay in their shared attraction to participatory governance models, exemplified by the concept of “council-based administration” (edareh shoraei). However, these initiatives proved short-lived as intensified factional conflicts, the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War in 1980, and a growing tide of cultural conservatism and authoritarianism ultimately led to the dissolution of most of these collectives and councils. Despite this, the legacies of these efforts endure, offering valuable insights for contemporary social activism.

Universities were at the forefront of the efforts to create democratic models of governance at workplaces. This essay examines professors’ efforts to dismantle the suppressive university bureaucracy by forming the National Organization of University Professors (NOUP) as a civic association, drafting a charter advocating for academic freedom and university autonomy, contributing to the revolution and even experimenting with a short-lived university administration based on elected councils. These efforts were enriched by the unique spirit of solidarity and imagination that often characterizes revolutionary periods, as also fueled the energy and inspired the creative power of the movement. Ultimately, the new regime’s consolidation of power through increasingly monopolistic and authoritarian practices extinguished the dream of a free and democratic university system in Iran.

As the NOUP exemplifies, academic freedom and university independence are inextricably linked. Academic freedom, which guarantees the collective freedoms of teachers and students thrives within a framework of university independence. The latter ensures that universities have the autonomy to make internal decisions, safeguarding their intellectual pursuits from undue societal or state influence.

The available information on the NOUP experience is limited for two reasons: First, the expulsion and exile of its founding members hampered efforts to document its history. Second, scholarly research in and outside Iran largely focused on 1980s Cultural Revolution and the subsequent transformation of universities. The single source of information about this organization is a written interview conducted in 1999 with Nasser Pakdaman (1932–2023), a founding member of the organization.[2]Except for Mojab (1991) the story of the organization remains largely ignored in scholarship on the Cultural Revolution, even the recent studies (Special issue of Cheshmandaz-e Iran, 2021; … Continue reading To learn more about the organization, I decided to do some personal research and talk to some members. Farhad No’mani and Sohrab Behdad, who together with Pakdaman formed the founding core of the organization at the Faculty of Economics at the University of Tehran (UT), accepted my invitation to speak with me about their experiences, as did Guiti Etemad, a representative of the Faculty of Architecture of the National University. I hope this paper and dialogue around the NOUP encourage others, particularly those joined the organization from different cities and universities to document their experiences and enrich our knowledge about this period of university history in Iran.[3]Pakdaman refers to some of the NOUP’s members who discussed their views in Education and Culture, a quarterly magazine published in Shiraz during 1979-80. He also mentions that Kavoshgar, a journal … Continue reading

Political Openings and Young Faculty Drive in Building Association

Pakdaman echoes arguments from historians of the revolution, contending the Shah’s 1977 limited liberalization backfired, triggering a chain reaction that culminated in the revolution. The policy of limited liberalization was never intended as real democratization project. Crackdowns further exposed this insincerity, exemplified by the order banning veiled students from campus that same year. (Pakdaman, 1999) Government’s three additional interventions in university affairs during 1977 solidified the growing solidarity between professors and students. First, the transfer of Aryamehr University of Technology (AUT) from Tehran to Isfahan, without consulting the faculty, aimed to weaken the university’s contribution to the student movement. The second decision was to appoint Colonel Valian as a member of the UT’s Private Law Department, without obtaining the department’s approval, an act that fueled rumors of appointing military commanders as university heads. The third decision was to instruct the UT administration to close students’ libraries. These libraries, often occupying a small room, functioned as sites for political socialization and exchange of radical political texts and government-banned books.

Pakdaman (1999) argues that these interventions, set against the backdrop of a shifting political climate, spurred faculty members to break with routine and voice their objections. A case in point: the scientific council of the Faculty of Economics at UT wrote a letter of objection to the dean questioning the decision on student libraries. This act was “an unexpected and unprecedented step in solidarity with students” and signaled a turning point: “the wall is collapsing.” The 1977-78 academic year began with the Writers’ Association poetry’ evenings (October 28 to November 8, 1977) in the Goethe Cultural Institute. This ceremony inspired great courage among the ranks of students and intellectuals. The momentum continued at AUT by university hosting its own new series of poetry evenings throughout November and December. However, the incidents took a violent turn on December 6th when a demonstration around the university erupted, leading to students being beaten, deaths, and the attack of two Writers’ Association members by SAVAK agents. AUT students started a strike which was supported by their professors.

This influx of young, politically active professors reflected a changing social and political demographics of the Iranian academia. Many of them, graduates of US universities and hired by newly established technical universities, pushed for reforms and challenged established conservative routines. They had developed new courses and programs through scholarly interactions between technical and social sciences universities. Behdad who began teaching in the early 1970s at both the Faculty of Economics at UT and the Department of Industries at AUT, notes that AUT professors and students were eager to learn about economics and political issues and even supported new publications in these areas. The university extended an invitation to Khuwarizmi Publishers to collaborate on the establishment of its press, and Behdad was asked to oversee the publishing of essential books on economic theory and thought.[4]According to Behdad, a group of the best translators worked with him on this project and only in two to three years could they publish proper translations of some essential texts in economics. These … Continue reading

Guiti Etemad and Mehdi Kazemi Bidhendi, both teaching at the National University’s Faculty of Architecture since 1972, took the initiative to invite a team of social science professors, including No’mani, to collaborate on establishing a master’s program in urban planning that incorporated a critical political economy perspective. (Etemad, 2024) No’mani points to a generational gap among social science professors, with faculties dominated by older scholars exhibiting a more conservative bent. He suggests this caution stemmed from a more serious consideration of the government’s repression, leading to a less optimistic outlook on political change:

Shah’s establishment of the Rastakhiz Party in 1975, with its forced registration, deeply discouraged many of them, including professors leaning towards the Third Force. Some even feared a rise of fascism. Pakdaman himself felt depressed. But I initially believed the situation couldn’t worsen, with or without the Rastakhiz Party. Pakdaman became surprisingly energized as the political environment opened up slightly, allowing him to flourish. (No’mani, 2023)

The letter of objection to the ATU’s move to Isfahan, signed by 138 faculty members of the university in February 1977, was a sign of the strong spirit of protest among the professors in this university. The AUT professors’ protest letter followed by their general strike stands as one of the most significant responses to government intervention in university decision-making in Iran’s recent history. Pakdaman argues that professors’ blatant disregard for government instructions regarding the AUT transfer and spring 1978 student enrollment marked “the first sign of the emergence of dual power in the revolution.” These interactions and solidarity events in 1977 paved the way for the first meeting of the NOUP.

During the spring months of 1978 (1357), a small group of no more than a few hands of university scholars gradually gathered to consider forming a professional organization. The core group consisted of three professors from the Faculty of Economics at UT, two professors from its Faculty of Engineering, two or three professors from ATU, and one professor from the National University. However, there were others who attended one or two meetings, or colleagues from universities in the provinces (Hamadan, Shiraz, etc.) who joined the discussions when they came to Tehran. (Pakdaman, 1999)

Professors from the Faculty of Economics included Nasser Pakdaman, Farhad No’mani and Sohrab Behdad; Farzad Biglari and Hassan Abaspour came from AUT, Iraj Farhomand, Ostad Hosseini and Sadegh Zibakalam joined from UT’s Faculty of Engineering; Sima Kouban from the Faculty of Fine Arts and Kazemi from National University attended the meetings. No’mani remembers a surge in morale for political change driven by the release of political prisoners due to the limited liberalization. Recognizing the potential of the released prisoners, he discussed with them the importance of forming a united political front. He pointed to the initial steps already taken by the NOUP as an example. His efforts helped to win over their supporters into the circle of NOUP scholars.

From Vision to Consensus: Crafting a University Charter

Drafting a charter was already on the agenda when professors met in the spring of 1978: “A charter should be written to outline our vision for the university and what we want for its community; The signature of those who agree to the charter should be secured and the first steps towards establishing a faculty association should be taken.” The draft charter was ready in July after several weeks of work and meetings usually held at homes. Later, the NOUP held its public meetings at the UT professors’ club. The founders of the NOPU were serious about maintaining the heterogeneous political composition within the organization. This commitment to inclusivity, a rare and insightful approach at the time, fostered the NOPU’s resilience and amplified its impact on the surrounding environment. However, collaborating with this diverse range of thinkers was not without its challenges. No’mani recounts an instance of a professor who participated in the faculty sit-in at the UT Secretariat office [on December 20] but harbored reservations about its political heterogeneity. He expressed his doubts to No’mani questioning Pakdaman’s potential support for Bakhtiar, the last prime minister under the Shah. “He did not know Pakdaman at all and did not understand his commitment to this collective endeavor… They later learned to appreciate the value of Nasser Pakdaman.” (No’mani, 2023)

The group involved in drafting the charter consisted of 20-30 individuals, with different political affiliations. Pakdaman invited members of the Third Force [Niroie Savom] and National Front, including some professors from the Faculty of Law and Political Science. Among them was Hamid Enayat. He usually did not sign the petitions and statements, while was active in the National Front. We had professors who were affiliated with Sarbedaran[5]The Union of Iranian Communists (Sarbedaran), a group adhering to Maoism, actively opposed the Shah’s regime. Initially, they aligned with the pro-Khomeini faction of the Islamic Republic … Continue reading, mainly its younger members. Beiglari, from the AUT made occasional appearances, while Iraj Farhomand, a renowned expert in his field from the Faculty of Engineering at UT and a member of the Ranjbaran,[6]Founded in 1979 through the merger of nine Marxist organizations, the Ranjbaran Party initially supported the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan and endorsed the 1979 Islamic Republic referendum. … Continue reading participated more regularly. Hassan Abaspour, a AUT professor who was affiliated with the Islamic groups, was open- minded and attended the meetings held at home.[7]Abaspour’s Wiki page mentions that he was a member of the NOUP’s temporary board of directors. A friend of [Ayatollah] Beheshti, later he joined the government as minister of energy. The professors associated with Mo’talefeh were narrow-minded. (ibid.)

Pakdaman describes the charter as a concise document with a brief introduction that serves as “a forceful statement on the critical assessment of the existing university system” followed by four key articles outlining the organization’s goals. The charters four articles advocated university autonomy, democratic principles within the university structure, academic freedoms, and finally, the social security of university staff.[8]According to Pakdaman (1999): “The charter’s language, though constrained by the oppressive climate of the time, managed to express its message directly without resorting to coded references … Continue reading No’mani describes the disagreements raised in one of the meetings held for drafting the charter:

The name of the organization was debated at the June meeting. Something like a democratic organization of professors’ was proposed by the left-wing professors. Enayat said it was important to have the word ‘national’ in the name. The word “democratic” had a leftist connotation. He got up to leave in the middle of the meeting. We talked to him and convinced him to return. Some said that a vote should take place… I said that it is more important to bring all views together and that the content is more important than the form; The National Organization of University Professors was approved… In fact, pro National Front professors were tougher than others. No one suggested adding the word ‘Islamic’ to the name. Maleki was very active in those days. (No’mani, 1402)

The draft of the charter was presented and discussed at a conference held at AUT on July 25, 1978, titled Crisis of Iran’s Higher Education. More than 150 faculty members attended the conference, and its resolution mentioned the key articles of the charter and the called for the establishment of the professors’ organization. The charter was released publicly after the conference to make it accessible to all academics to sign and join the organization. However, the list of the names and number of those who signed the charter are unfortunately not stored or remembered. Behdad, who had maintained the list of the signatories for several years, says:

The focus wasn’t on the number of signatures, as our priorities were its impact and ensuring broad contribution from all groups. Within NOUP, professors held diverse viewpoints. Some sympathized with the Mujahideen, while others entered the post-revolution government. Sometimes the active core of the NOUP was pro-Fadaei professors, sometimes was pro-Mujahideen or the Union of Communists… We avoided official stances on specific political issues, including the US embassy occupation, to foster collaboration on shared principles. (Behdad, 2024)

However, No’mani (2023) argues for a nuanced understanding of the organization’s founding. While acknowledging the social capital of the founders in its initial launch and mobilization, he emphasizes the importance of the political capital of the Fadaei guerrilla organization in strengthening the NOUP as a historical fact. This highlights the interplay between social and political factors in the organization’s development.

I always thought that it was not important that the names of political organizations were mentioned in this story. Nasser also writes that there were different groups, including us economics professors. But if anyone wants to go back to the date and ask how it came about that a large group of professors gathered in that short period of time, it should be said that they joined this organization because of the support of professors who were pro-Fadaei Guerrilla. The hegemony was with them. At that time, I was in contact with dozens of professors at Iranian universities, and we met outside NOUP. We insisted that this organization be open and anyone who wants can join it. We did not believe that the Islamic professors who were critical of the system should not be among us. Maleki and others decided to come through their own students. (No’mani, 2023)

The NOUP’s formation galvanized support for the revolutionary movement and amplified the university protests. Upon taking office as prime minister on August 27, Sharif Emami assured his science minister, Hooshang Nahāvandi, that his government would back a bill that would grant universities autonomy. However, the bill was later rejected by the parliament.[9]For more info on this bill see: https://historydocuments.org/sanad/?page=show_document&id=ic89ko26a7c His government wavered between a clamping down on protests and making a political retreat. While a massive demonstration on Eid-e Fitr in Tehran received a permit and millions of people could show their support for the religious leaders, the military was granted permission to shoot peaceful protestors on another demonstration on September 8, called later Black Friday. The NOUP did not get a permit for holding a congress, so they decided to invite only the representatives, two or three people from each university to gather in a meeting at Tehran Polytechnic University: “Over forty representatives from universities and colleges in Tehran and other cities attended the meeting. These included the universities of Shiraz, Tabriz, Isfahan, Mashhad, Jundishapur, and Hamadan as well as the colleges of Gilan, Babolsar, and Qom.” (Pakdaman, 1999) “Kazemi Bidehandi, volunteered from the Faculty of Architecture, and Rafii represented the Faculty of Science, and Farahbakhsh joined them later, all three from National University.” (Etemad 2024)

The representatives elected the 9 members of the interim board of directors, five from universities located in Tehran and four from universities in Shiraz, Ahvaz, Mashhad, and Tabriz. With martial law in effect and the revolution still unfolding, the NOUP could not hold a congress in 1978. Therefore, the interim board led the organization throughout that year. Despite the political turmoil, student-organized large lectures provided invited professors a platform to connect with colleagues at other universities and expand their professional networks across the provinces.

We inquired about prominent professors in other cities through our students and contacted them directly. When the second round of NOUP meetings started, we had a representative from the College of Babolsar, one or two people from Shiraz [University] and a professor from Bu-Ali Sina University in Hamedan, his name was Navidi, and he was Kurdish. Some attendees, recently hired at universities, were former student activists of the Student Confederation. Jundishapur University in Ahvaz and Petroleum University in Abadan also sent representatives. Notably, Tabriz University, with a perhaps older faculty, had a lower level of participation. (No’mani, 2023)

Behdad (2024) also highlights how younger faculty leveraged their social networks to gather signatures: “When we drafted the charter, I first approached friends from the AUT to sign. As I knew half the professors in physics and was familiar with those in computer science, electrical engineering, civil engineering, and mathematics, it helped. Additionally, professors at AUT had close connections with the Faculty of Engineering at UT, which facilitated further outreach.” No’mani notes the limited female participation in NOUP’s early stages: “Guiti Etemad and Sima Kouban were part of the core group of 20, 30 professors, but Homa Nategh ignored the NOUP’s invitation because she considered herself more political. Over time the number of women grew.” Etemad also highlights the participation of women in NOUP, noting that of the 66 professors who took part in the sit-in at the building of Ministry of Science[10]The Ministry of Science has undergone name changes in recent decades. Following the 1979 Revolution, it became the Ministry of Culture and Higher Education. In 2000, it was renamed to its current … Continue reading in January 1978 only six were women. At that time, 15 percent of university professors were female.

The Week of Solidarity: Solidarity becomes a Word of the Revolution

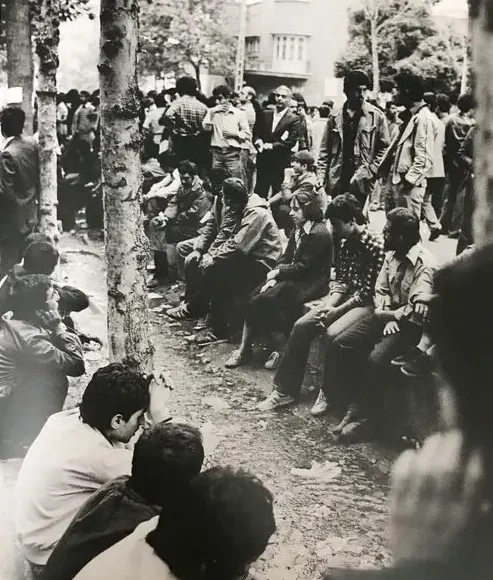

The NOUP initiated the Solidarity Week from November 6 to 11,1978 as a platform to invite writers, poets, journalists, political prisoners and representatives of various groups and communities to come to the UT and give lectures to the audience on the university’s large lawn, as the venue of the event: “Solidarity became a word of the revolution.” Solidarity Week was also observed at universities in other cities, where dozens of intellectuals and political activists delivered speeches. The resolution, issued by the NOUP and read at the ceremony’s conclusion, called for the lifting of martial law, the release of political prisoners, press freedom, the dismantling of repressive university structures like security offices and guards, university autonomy, and the reinstatement of expelled professors and students. (Pakdaman, 1999) The challenge of bringing diverse political groups together became apparent again during Solidarity Week. No’mani, who was responsible for the event program, invited a wide range of intellectuals, activists, and released political prisoners to speak. However, cooperation wasn’t seamless: “I did not want to speak myself. Homa Nategh also refused. Azam Taleghani and Vida Hajebi were scheduled on the same day. After Taleghani’s speech, I approached Hajebi to speak next. She said why should I speak after her… The schedule had been announced and I had no other choice but asking Nasser to talk to her. He knew her language better and he was able to get her to the podium to give her speech.

The senior pro Tudeh professors did not attend in the solidarity week ceremony. No’mani who knew some of them in person suggests that some of them had single-minded spirit and their general lack of belief in trade union-political activities, and especially at that time, cooperation with the national and liberal forces against the Islamists. No’mani, who was personally acquainted with some of them, suggests that their reasons were multifaceted. “Some of them were individualist and teamless players, some other avoided open political involvement. Additionally, they were reluctant to collaborate with national and liberal forces against the Islamists, particularly at that time.” Paivandi (2024), then a UT social sciences student, confirms that this group of professors considered Pakdaman as a “liberal” [vs pro-Khomeini] and did not like working with him.

The NOUP, in collaboration with the Writers’ Association and the Committee to Defend Political Prisoners’ Rights published a newsletter (Hambastegi) and distributed it through the university network, when the progressive journalists decided to go on strike. They also joined the Public Sector Orgs Central Council (Shoraye markazi hamahangi sazemanhay dolati), a coalition of workplace strike committees formed to unify their decision-making. The public sector council played a pivotal role in disrupting the state functions during the fall and its strike committees inspired some the workplace councils emerged in the winter. The NOUP also supported the oil industry strike which began in October 1978: “In late December, one of the young labor activists living in Abadan along with one of my students came to my office at the Faculty of Economics. Those two told me the message of a group of project workers of Abadan oil industry, asking for financial assistance for unemployed and striking workers. I shared the message first with Pakdaman and then with the NOUP board of directors. They agreed to help with enthusiasm. In less than a week, a significant amount of money was collected, and I went to Khorramshahr by train to deliver it with that young man and a small suitcase full of bills, and then to the house of an oil industry worker in the working-class area of Abadan. (No’mani, 2023) The NOUP base at the UT professors club became a central hub for coordinating strikes, protests, and other acts of resistance that emerged from the population in fall 1978 and early 1979. Behdad (2024) notes:

Our base at the UT club transformed into a critical center for the movement. Strikes were erupting throughout the city, and strikers did not know how to end it; Obviously the strike could not continue forever. Nasser was wonderful in organizing these matters; He’d send us to ongoing strikes to work with participants, helping them formulate resolutions, define their demands, and ultimately negotiate an end to the action. This freed them to pursue other necessities. As our influence grew, the base became increasingly bustling. One day, a vanload of documents might be carried to our base from an embassy; the next, the head of a government office or even a Savak agent might be brought before us, seeking guidance on how to handle the situation. The level of trust and responsibility entrusted to us was truly remarkable!

On December 20th about a hundred professors started a sit in the TU secretariat building, to call for the reopening of the universities. Three days after that more than sixty professors from several other universities started another sit-in to support them in the Ministry of Science building on Vila Street. Guiti Etemad, a participant in this sit-in, recounts the tragic killing of a young professor during the protest:

Discussions were hot in the hall. Kazemi was in constant discussion with [Hassan] Ghafourifard [Polytechnic professor and member of the Mo’talefeh]. Mahmoud Kashani was also in the sit-in, the son of Ayatollah Kashani and he started defending his father in the debates,[11]Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani, a Shia cleric and head of the Iranian parliament in 1953, is alleged to have played a negative role in the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh.… Isa Kalantari, the brother of Musa Kalantari, was also in the sit-in. Kamran Nejatollahi was only 24 years old and was an assistant to Professor Asgari at the Polytechnic University. I think the office we occupied for the sit-in was on the 7th floor. It had a balcony and Nejatollahi was on the balcony when they shot him from the opposite building which belonged to Rastakhiz Party. The frantic search for a blanket and the struggle to open the stuck elevator door caused a significant delay. Finally, we managed to send him to the hospital… I think they wanted to break the sit-in because they attacked the sit-in at ten-eleven the same night; the Imperial Guard attacked and shot blindly. Each group had crawled to a corner of the hall; One of the professors told “let’s chant long live Shah!” Everyone muffled his voice… When they stormed our floor, they used their batons and guns to subdue everyone. They then forced us down from the seventh floor. Reaching the street, I saw Kazemi had suffered a head injury. They then loaded us into prisoner transport vehicles and took us to the Jamshidiye barracks at the end of Fatemi Street. We were released the following evening, after Nejatollahi’s burial and funeral ceremony. (Etemad, 2023)

The NOUP decided to propose a date for the university reopening; The week of January 20-27th was announced. Many civic organizations supported the decision and Ayatollah Taleghani joined their call. The UT reopened on January 23rd to a massive celebratory ceremony. In the wake of numerous university presidents resigning or removal, NOUP proposed a ‘transitional administration’ plan. This plan called for a joint council of students, academics, and administrative staff to take over the university’s management. (Pakdaman, 1999)

The University Councils: Purges and Power Struggles

The prominent cleric, aiming for public visibility, chose to turn the UT into the platform of their activities. Forty clerics staged a sit-in at the UT’s small mosque which sparked the formation of a welcoming committee to prepare for Ayatollah Khomeini’s return to Iran. The NOUP expressed its support for the sit-in through a statement, praising “the solidarity between the clergy and academics in the fight against oppression and tyranny.” Prime Minister Bazargan also chose the UT as the venue to announce his government program.

Collaborating with the welcoming committee, the NOUP ensured the ceremony’s smooth execution. Despite these collaborations, when NOUP presented its proposal for council-based university management, the interim government disregarded the plan and instead appointed some of the NOUP members[12]The other three members included Hossein Sabaghian, Torabali Baratali and Kazem Abhari. They were also a member of NOUP. (Sharafzadeh Brder, 1984: 169-170), including Mohammad Maleki who served at its board to form the UT’s Board of Trustees in late February. (Sharafzadeh Berdr, 2014:173) “A wave of cold anger had taken over everyone, especially since these four people were all first-rate members of the NOUP who had not even bothered to inform the other members.” (Pakdaman, 1999) The new science minister also sidestepped the calls for establishing the councils and unilaterally appointed university and college presidents. The NOUP issued an objection letter on these top-down appointments on March 8th.

The newly appointed presidents inherited a turbulent environment at the universities. They were under huge pressures from the student body, both leftist and Islamists, to dismiss significant numbers of the professors associated with the previous regime. (Ghaed, 1980) At the same time, they had to address tensions arising from the Islamic students’ attacks on the leftist students aiming to hinder their growth. They were even deprived of the strategic support of the government because there was a fight on proper university reform policy among the powerful bodies of the Islamic Republic (IR). Shariatmadari, the moderate Minister of Science was critical about purging a high number of UT professors by Maleki but was supportive of him when the board tried to curtail the increasing power of the Islamic Associations of Students (IAS) at the university. IAS students demanded more radical and Islamic leadership and objecting to activities of the non-Islamic students on campus. They disrupted the NOUP’s general assembly meeting at the UT in June 1979.

On June 23 and 24, NOUP hold a two-day conference at the AUT to discuss the conditions of the universities after the revolution and examine the path to independence at universities. The conference hall displayed banners with messages like “Let academics guide the university!” and “Universities can’t be truly independent without democratic practices.” Pakdaman and Minister of Education gave the opening speech, and 300 professors participated in the debates running for two days. In one of the panels the representatives from universities of Tabriz, Azad, Polytechnic, National, and Science and Technology presented their proposals for an alternative university system. According to Ettela’at Newspaper, all proposals suggested that Ministry of Science be replaced by central universities council. The attendees also lamented the slow progress of establishing councils at their universities, blaming it on the lack of cooperation from appointed presidents. (June 18, 1979: 11) The final session grew tense on several occasions during discussions regarding the resolution’s articles. More than a resolution, this document served as NOUP’s new charter. Responding to the ideological challenges of the post-revolution era, its opening paragraph declared the university a “bastion of freedom,” where the academics, free from the constraints of “inquisition and dogma,” could pursue transforming the university system. (Pakdaman, 1999) A key item from the conference resolution dominated Ettela’at’s front page: “Include the university independence in the Constitution.” The draft of the new Constitution was published the same day. University councils were central to NOUP’s reform proposals, but the entire political establishment, including the interim government, viewed them with skepticism. Concerns were both political and practical, regarding their potential challenges for the political system and university bureaucracy.[13]Shariatmadari tasked professors at the UT’s Faculty of Law to develop a proposal for an independent university system. This proposal faced the fierce opposition of the IAS members, while it did not … Continue reading

This period saw even moderate members of the Revolutionary Council worried about the outcome of university tensions. In a July meeting, while discussing the perceived lack of radicalism in the interim government, the higher education ministry became a point of contention. Ezatollah Sahabi, a left-wing Islamist, even criticized Minister Shariatmadari and expressed concern about the influence of NOUP on his decisions. He notes: “Dr. Shariatmadari is intrigued by the NOUP.” (Nabavi, 2021) In separate sessions of the council, some members even suggested not opening the universities in the new academic year. Others, however, dismissed concerns about leftist students, arguing there is always an option of bringing “the Islamic youth to defend the revolution at the university.” (Alibabaei, 2003: 467-468)

Despite their limited societal power, leftist student groups held a strong influence within the universities and the council system, as envisioned by NOUP, could have further solidified this dynamic. The scattered evidence on student representatives in the councils also supports that pro-Fadaei and Mujahideen students had a strong hold on the councils of the key universities.[14]Among those evidence is a report by then a Pishgam (supporter of Fadaei organization) student who writes Pishgam won 30-35 percent of the votes of their councils, while the Muslim Students (supporter … Continue reading The councils were formed in all faculties and departments of the UT when the 1979-80 academic year started. Other universities followed the suit if the NOUP had influential members among the faculty. Composed of 3 professors, 3 students, and 3 employees of each faculty, the councils were to elect the dean. Maleki notes that UT Board endorsed all the elected deans, including the leftist figures such as Mohammad Reza Lotfi, the professor and artist of the Faculty of Fine Arts. No’mani (2023) describes the council of the Faculty of Economics at the UT:

Manouchehr Kiani, Behdad, and I served on the council. I took on the responsibility of the education and began inviting prominent researchers who had returned to Iran to contribute to our students’ education through lectures or teaching positions. I invited researchers like Khosro Shaakeri and Mahmoud Rasekh. In one of our meetings the issue of purging professors and staff was brought up by the students. I argued against it, maintaining that a professor’s expertise is paramount, and their political views shouldn’t determine their eligibility to work at the university. Maliki had already dismissed Dr. Meshkat. The UT Board informed each faculty about the list of dismissed professors. Maliki did some positive changes, but his tenure was also marked by wrong decisions. Though the number of expulsions at the UT was apparently lower compared to other universities.

The November 1979 seizure of the U.S. Embassy by pro-Khomeini students led to the interim government collapse, which represented the moderate Islam in the new political regime and weakened the power of the UT Board and other appointed university presidents. The takeover emboldened the students to initiate “unilateral actions” against rival political forces inside the government and radicalise the IR politics with a general intolerance of dissent elsewhere.

The Cultural Revolution and Rerailing the Universities

In early 1979, some intellectuals and academics wrote with irony, sometimes with wonder about the IR’s position change on university, calling it an “anti-revolutionary bastion” rather than stronghold of the revolution. (Barahani, 1980: 49) Some struggled to understand how the Islamic left, despite maintaining distinct and often conflicting positions on economic and political issues, aligned with the conservatives on university system. The November 1979 seizure of the U.S. embassy was a watershed moment, drawing public attention to the rise of Islamic leftist forces within the IR. It “fueled a surge of anti-imperialist sentiment and forged a temporary truce” between secular and Islamic leftist groups, delaying their confrontations at the universities (Ghaed, 1980). While the embassy takeover and subsequent collapse of the interim government should have signaled the end of the post-revolution’s relative political openness, most secular and leftist intellectuals likely underestimated its long-term impact. They couldn’t have foreseen how the event would solidify a conservative cultural agenda, uniting a broad spectrum of clerics and Islamic factions. The signs of the political realignment emerged with 1979 presidential election, when Khomeini banned clerics from running in the election. The ban opened the door for Abolhassan Banisadr, a moderate Islamist, to win the election. The Islamic Republic Party (IRP) expressed dissatisfaction with the election results in a letter to Khomeini. They invoked rhetoric about the 1906 Constitutional Revolution and warned they feared the return to a secular state and a weakening of the religious authority. They wrote that modernists “despite their conflicts, have become complicit in expelling Islam.”

The coming months witnessed a dangerous conflation of anxieties about the threat of modernity to Islam with anxieties about universities as bastions of leftist thought. Both became targets of relentless attacks in Khomeini’s speeches and public statements.[15]See Shiraz University students meeting with Khomeini on 6 June 1979, also UT students meeting on 13 June. In these speeches, he would emphasize: ‘if you see someone you suspect is a communist, … Continue reading

Hassan Ayat, the political secretary of the IRP, used the conflation to frame the university closure agenda. In a meeting with Islamic students, Ayat argued:

Non-Islamic professors must be dismissed; the call for the dismissal should be raised from below. They [students] should say we don’t want non-Islamic [professors]; Say that they should go and do something else… The communists will be absolutely removed. About Mujahideen who have Islamic title, they also should be suspended… Universities, with current state, should be shut down entirely.[16]According to Hazeri (2000:92), the recordings of the meeting with Ayat leaked to the newspapers: “The leak of the discussions and decisions moved the events up and intensified the confrontations. … Continue reading (Ayat, 1980)

The Islamic students aligned with Ayat would argue later the influence of secular left students did not reflect their societal representation: “while these groups enjoyed 30-40 percent student support, their societal power was close to 5 percent, and the university makeup should reflect that.” (Hazeri, 2000: 88 and 92) Some other Islamic students argued the political freedom at universities would waste their time. They rather want to be free to contribute to practical projects and technical improvements to consolidate the revolution. The University of Revolution journal, published by the Cultural Revolution Headquarter (CRH), would brim with reports on students’ scientific projects, aimed to tackle the pressing problems plaguing industries and the service sector after the revolution.

“On April 13, the Islamic Republic Party convened a two-day seminar at the Faculty of Theology titled ‘Critique of Political Activities and Pluralism in the University’ (Farastkhah, 2005: 45). The event aimed to establish consensus for the party’s new discourse on universities.

The universities were officially closed in May 1980 and CRH formed on June 16, when Khomeini appointed some of the prominent Islamic intellectuals and cultural figures as its members.[17]Ali Shariatmadari, Mohammad Javad Bahnar, Mehdi Rabbani Amalshi, Hassan Habibi, Abdul Karim Soroush, Shams Al Ahmed, Jalaluddin Farsi were assigned as the first members of the CRH and Ali Khamenei … Continue reading Many of these Islamic scholars later conceded that their attempts to create Islamic social science textbooks for universities had been unsuccessful. (Zibakalam, 1999) However, as secular intellectuals who were observing the government’s crackdown on universities argued, the focus on social science textbooks missed the mark because: “Technical universities have been just as embroiled in these conflicts as humanities departments, and often even more so.” (Ghaed, 1980:4) The CRH instituted a formal ideological screening process for the hiring committees, which with some modifications, remains in place in the university recruitment system. The hiring committees reject the candidates if deemed to fall into one of these categories: “adherence to atheist ideologies, affiliation with counter-revolutionary forces, ties to the Pahlavi regime, or moral transgressions.”[18]Mostafa Moeen (2012), who served at the CRH faculty selection committee back then but joined the Khatami cabinet confirms they relied on these criteria but replaces “animosity with the … Continue reading (Hazeri, 2000: 105)

The process for dismissing professors varied across faculties. Behdad describes the experience at UT’s economics department as more “respectful” compared to the National University: “They told us you can do your research projects and send us a monthly report. But at National University, the situation was harsher, with reports of even professors’ offices being seized…. I continued to go to university and do my own work for a year or two, but it didn’t make sense to continue. I was ultimately dismissed in 1983, for what they claimed was work absence.” (Behdad, 2024). Similar to Behdad, No’mani and Pakdaman were first prohibited from teaching before receiving official dismissal letters. Guiti Etemad recounts a similar experience:

Initially, they told me I could continue teaching but wouldn’t allow me to be a group manager. But when the university was closed, I received a dismissal notice citing me as both a communist and a Zionist, a contradictory accusation that left me bewildered. We had a student named Shoeibi who became vice president after the university closure. I received a call from his office a year later, asking why I left my work and telling me I could return. But going back was simply out of the question for me. Kazemi also faced dismissal based on similar accusations. This effectively dismantled our entire urban planning group. The remaining contracted professors saw their work rejected as well. (Etemad, 2023)

The university closure marked the end of the NOUP’s activities. Pakdaman (1999) describes a chilling dismantling: “The organization slowly slowed down and gradually ground to a halt. Many of its members faced dismissal; A group of them took the path of exile and immigration, some were imprisoned, and some were handed over to the death squads.” Though NOUP membership itself didn’t lead to arrests, the universities faced violent attacks in May 1980 which resulted in deaths and injuries among both students and faculty. The exact number of those who perished during the crackdown remains unknown. Nasser Mohajer’s research identified 37 students who lost their lives. (2018:12)

A stark comparison between faculty numbers in 1979 and the first year of the university’s reopening (1982-83) reveals a significant decline. Data suggests that approximately 7,800 professors, representing 46 percent of the 1979 faculty, were not reinstated in 1982. This aligns with Saeed Paivandi’s (2022) observation of roughly 6,000 dismissed professors.

The selection process extended to students as well, with a reported decrease of 57,000 students during this period. This implies a substantial impact on the overall student body. The similar dismissal rates for male and female faculty and students suggest a fair treatment by the committees. (Houshmand, 2021: 196) In a joint statement issued with other civic associations in May 1980, the NOUP condemned the violent attacks on universities. The statement reads:

We hold the government accountable for the tragedies and call them to be accountable to people by responding to following demands: 1) The perpetrators of the recent violence must be identified and brought to trial. 2) All university students, professors, and staff currently under arrest should be released immediately. 3)The establishment of university councils and academic freedom should be guaranteed. (Andiseh Azad, 1980)

Conclusion

Emerged out of the 1978 revolutionary movement, the NOUP was a spontaneous and inclusive organization which championed the ideals of academic freedom and university self-governance, placing them at the forefront of the revolutionary agenda. It remained steadfast in its commitment to democratic principles despite the fragmentated political landscape of the post-revolution era. The NOUP left a legacy that could be inspiring for academics today.. Their success stemmed from three key factors: NOUP drew in young, progressive professors from across Iran’s academic sphere. The founding members placed a strong emphasis on political and ideological inclusivity, fostering a diverse and vibrant organization. and finally, the NOUP effectively bargained with political forces and parties to safeguard its independence. The fate of the NOUP mirrors that of many other civil society organizations during this tumultuous period. With increasing political uniformity, the state consolidated its power through a series of events – the embassy takeover, the Cultural Revolution, and the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War in September 1980. This consolidation squeezed out the political rivals and independent civil organization. However, it is important to acknowledge what set NOUP apart from other organizations. Unlike others, NOUP bridged ideological divides, bringing together professors from various schools of thought to work together to build a better university. it is an irony that 1979 Revolution made the emergence of the NOUP possible and at the same time ruined the very first freedoms required for its functions through subsequent government power consolidation. The NOUP story is about the moments of liberation and breaking down the walls of tyranny while the ideological, social and economic walls that frame the social divides are not represented properly at political landscape.

References

Alibabaei, Dawood. 2003/1382. What happened in Iran in 25 years? Tehran: Omid Farda Publishing House.

Ayat, Hassan, 1980/1359. Wikipedia page. https://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Barahani, Reza. 1980/1359. “About the cultural revolution”. Andishe Azad, 2: 42-48.

Behdad, Sohrab. 1997/1376. “Cultural Revolution under the Islamic Republic: Islamization of economy in Iranian universities”. Ankash Magazine, No. 13.

Kanonhaye Democratic. 1980/1359. “Joint statement on universities”. Andishe Azad, 2: 3-6.

Farstakhah, Maghsood. 2006/1385. “In the name of culture, to the benefit of politics”. Nameh, 49.

Farooghi, Hassan. 2021/1400. “Tazkeih committees: dismissals before the Cultural Revolution”. Iran Perspective, 3: 241-227

Ghaed, Mohammad [pseudonym: M. Morad]. 1980/1359. “The last page of the calendar.” Ketab-e Jom’e, 32: 10-3.

Golkar, Saeed. 2008/1387. “State-university relations in the post-revolution Iran: 1978-2005.” PhD Thesis, Faculty of Political Science, UT. 1387.

Hazeri, Alimohammad. 2000/1379. “A reflection on the causes and consequences of the Cultural Revolution.” Matin Research Journal, 8: 106-81.

Houshmand, Ehsan. 2021/1400. “Investigating the process of the Cultural Revolution”. Cheshmandaz Iran, the special issue on Cultural Revolution: The university in suspension. 6-203.

Jandaghi, Farnoosh. 2023/1402. “The ‘University’ That Never Became.” Herfe/Honarmand, Ordibehsht 1402.

Maleki, Mohammad. 1999/1378. “No one asked us for an opinion.” Lowh Monthly, number 7.

Moeen, Mustafa. 2012/1391. “Mustafa Moeen’s untold stories about the Cultural Revolution.” Tarikh-e Irani website.

Mohajer, Nasser. 2008/1387. “1980 Cultural Revolution.” In The Inevitable Escape: Thirty stories of escape from the Islamic Republic of Iran, by Rousta etal. Paris: Noqteh Publication

NOUP. 1979/1358. Statement. Bamdad, 48:3, quoted by Houshmand, 2021: 45.

Nabavi, Seyed Abdulamir. 2021/1400. “The Revolutionary Council and the university question: Re-reading the Revolutionary Council minutes 1978-1980.” Motale’at-e Daneshgahi, 1(2): 109-134.

Paivandi, Saeed. 2024. Interview with Global Iranian Studies Review. 1-2.

———–. 2022. “University autonomy, academic freedom, and the government.” Andishe Azadi,12: 23-49.

Pakdaman, Nasser. 1999/1378. “National Organization of University Professors and revolution in Iran.” Etehad Kar, 58 and 60: February 1998 and April 1999.

Sharafzade Barder, Mohammad. 2014/1383. Cultural Revolution in Iranian Universities Imam Khomeini Research Institute.

Zibakalam, Sadegh. 1999/1378. “I officially and publicly ask for forgiveness.” Lowh Educational Monthly, 5: 22-33.

University of Revolution. 1981/1360. “University since the revolution: A report on Sharif University of Technology.” University of Revolution, 4: 24-39.

Endnotes

| ↑1 | I am indebted to Farhad No’mani, Sohrab Behdad and Guiti Etemadi who accepted my invitation to be interviewed about their experiences with the NOUP in winter and spring 2023. They generously gave several hours of their time to answer my questions via Skype and remote calls. I am particularly grateful to Farhad No’mani, who guided me through some of the labyrinths of this research and I found his insights concise and free of overused clichés. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Except for Mojab (1991) the story of the organization remains largely ignored in scholarship on the Cultural Revolution, even the recent studies (Special issue of Cheshmandaz-e Iran, 2021; Paivandi, 2022; Jandaqian, 2023. |

| ↑3 | Pakdaman refers to some of the NOUP’s members who discussed their views in Education and Culture, a quarterly magazine published in Shiraz during 1979-80. He also mentions that Kavoshgar, a journal published in New York City in 1987 and 1989 has a debate on the topic. I did not find none of these documents through internet search. |

| ↑4 | According to Behdad, a group of the best translators worked with him on this project and only in two to three years could they publish proper translations of some essential texts in economics. These included The Industrial Revolution by Eric Hobsbawm and Value and Capital by John Hicks. |

| ↑5 | The Union of Iranian Communists (Sarbedaran), a group adhering to Maoism, actively opposed the Shah’s regime. Initially, they aligned with the pro-Khomeini faction of the Islamic Republic particularly against its liberal Islamist rivals. However, their support shifted upon perceiving the dismissal of President Banisadr as a coup against democracy. Their armed uprising in Amol in February 1982, involving one hundred members, ultimately resulted in their downfall. |

| ↑6 | Founded in 1979 through the merger of nine Marxist organizations, the Ranjbaran Party initially supported the interim government of Mehdi Bazargan and endorsed the 1979 Islamic Republic referendum. They switched to supporting Banisadr while actively participating in the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). They opposed the government when Banisadr fled Iran and lost most of their members in the armed resistance in Fars and the northern provinces. |

| ↑7 | Abaspour’s Wiki page mentions that he was a member of the NOUP’s temporary board of directors. |

| ↑8 | According to Pakdaman (1999): “The charter’s language, though constrained by the oppressive climate of the time, managed to express its message directly without resorting to coded references or symbolic gestures. It avoided both religious rhetoric and excessive verbosity.” |

| ↑9 | For more info on this bill see: https://historydocuments.org/sanad/?page=show_document&id=ic89ko26a7c |

| ↑10 | The Ministry of Science has undergone name changes in recent decades. Following the 1979 Revolution, it became the Ministry of Culture and Higher Education. In 2000, it was renamed to its current title, the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology. We keep using the short name of the Ministry of Science for it. |

| ↑11 | Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani, a Shia cleric and head of the Iranian parliament in 1953, is alleged to have played a negative role in the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. |

| ↑12 | The other three members included Hossein Sabaghian, Torabali Baratali and Kazem Abhari. They were also a member of NOUP. (Sharafzadeh Brder, 1984: 169-170) |

| ↑13 | Shariatmadari tasked professors at the UT’s Faculty of Law to develop a proposal for an independent university system. This proposal faced the fierce opposition of the IAS members, while it did not even include the NOUP’s council system. In response to this conflict, Beheshti, leader of the Revolutionary Council, encouraged the IASs to draft their own proposal for university management. We see later that the IAS members finally called for the university closure and Cultural Revolution. |

| ↑14 | Among those evidence is a report by then a Pishgam (supporter of Fadaei organization) student who writes Pishgam won 30-35 percent of the votes of their councils, while the Muslim Students (supporter of Mujahideen) had 20-25 percent of the votes (Ali Samad 2001, quoted in Golkar, 2010: 94). Hazeri, then a member of the Islamic Association of Students also confirms that “30 to 40 percent of the student body were pro leftist groups.” (2000: 88) A report published by the University of the Revolution journal, affiliated with the Cultural Revolution Headquarter mentions the first council of the AUT composed of 10 pro-Muslim students and 5 pro-leftists, but the members of its second council (convened in fall 1979) were more pro-leftists. (1981: 31-31) |

| ↑15 | See Shiraz University students meeting with Khomeini on 6 June 1979, also UT students meeting on 13 June. In these speeches, he would emphasize: ‘if you see someone you suspect is a communist, whether teacher or president, throw them out of the university” or “I think these communists are pro-America.” (Sharafzadeh Bardr: 191) |

| ↑16 | According to Hazeri (2000:92), the recordings of the meeting with Ayat leaked to the newspapers: “The leak of the discussions and decisions moved the events up and intensified the confrontations. Islamic Associations had no other choice but to call for boycotting the classes.” |

| ↑17 | Ali Shariatmadari, Mohammad Javad Bahnar, Mehdi Rabbani Amalshi, Hassan Habibi, Abdul Karim Soroush, Shams Al Ahmed, Jalaluddin Farsi were assigned as the first members of the CRH and Ali Khamenei was its head. |

| ↑18 | Mostafa Moeen (2012), who served at the CRH faculty selection committee back then but joined the Khatami cabinet confirms they relied on these criteria but replaces “animosity with the government” for “the adherence to atheistic ideologies.” |

Comments are closed.