/Book Review | Reading Time: 6 minutes

Documenting Sea Change in the Persian Gulf

Scott Erich | December, 2025

Since 2020, I’ve been conducting ethnographic and historical research about property at sea in the lower Persian Gulf for my first book project, entitled Taming the Sea: Environment, Enclosure, and Extraction in Southeastern Arabia. My interlocutors in the book are largely fishermen from the southeasternmost states of the Arabian Peninsula: the United Arab Emirates and Oman. In Taming the Sea, my interlocutors and I ask and answer a fairly simple question: who, other than God, can possibly “own” the ocean? The answer, it turns out, can be quite complicated.

Figure 1: Underway in the Persian Gulf aboard a fishing skiff (Author photo, 2024)

Figure 1: Underway in the Persian Gulf aboard a fishing skiff (Author photo, 2024)

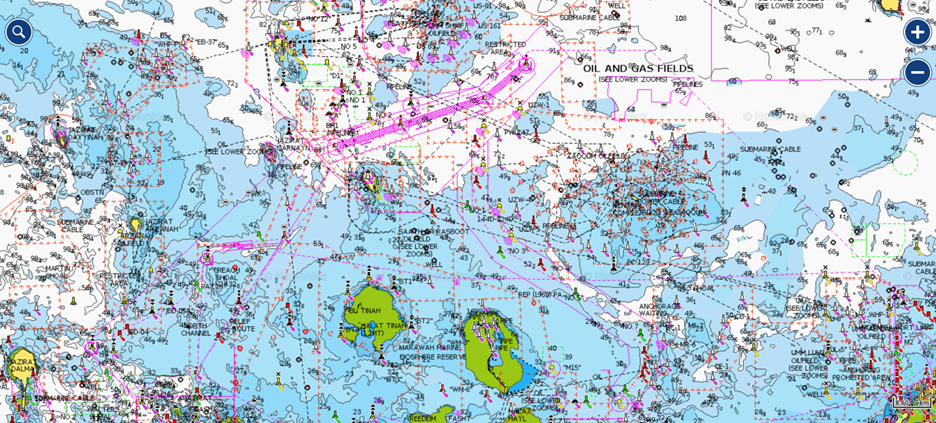

Offshore from the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, many people have attempted to enclose and own the sea in a variety of ways. Artisanal fishermen have relied on custom (‘urf) to create spaces where only they can harvest fish: fixed-net traps on the beach and proprietary reefs beyond the breakers. Oil companies have enclosed vast swaths of offshore space through concessions. Every wellhead, rig, loading terminal, or other floating infrastructure that extracts or circulates oil are surrounded by “restricted areas” with 500 meter radiuses at the smallest scale. At the largest scale, these enclosures are massive: the restricted zone around the drilling sites at Zakum oil field is equivalent to the area of Bahrain Island. Even beyond this scale, Exclusive Economic Zones – by far the largest enclosures of space on the planet here and elsewhere – have carved up the Persian Gulf in such a way that every single point at sea is someone (or some state’s) property.

Figure 2: The lower Persian Gulf (with Dalma Island in the bottom left corner and Sir Bu Nair in the top right) showing the extent of enclosure around Umm Al Shaif, Upper Zakum, and other oil fields. The red, orthogonal lines indicate the massive restricted zones. Map courtesy of Garmin/Navionics nautical chart software (https://maps.garmin.com/en-US/).

Figure 2: The lower Persian Gulf (with Dalma Island in the bottom left corner and Sir Bu Nair in the top right) showing the extent of enclosure around Umm Al Shaif, Upper Zakum, and other oil fields. The red, orthogonal lines indicate the massive restricted zones. Map courtesy of Garmin/Navionics nautical chart software (https://maps.garmin.com/en-US/).

My research follows fishermen to show how these and other forms of enclosure at sea are almost always partial. That is, they are habitually and consistently undermined at all scales. Some fishermen ignore the weight of tradition and fish in the otherwise inviolable areas protected by customary law, poaching from proprietary reefs and fixed traps. I have fished on skiffs with fishermen who violate the “restricted areas” around oil infrastructure, in part because they know that oil rigs, wellheads, and tankers act as fish magnets that attract schools of fish (and the predators these schools attract). I’ve also been with fishermen as they have transgressed borders at sea, fishing in the Exclusive Economic Zones of neighboring countries, often without so much as a second thought.

These and other cases show how the sea is very different from the land, even in the small, crowded, and militarized Persian Gulf. On land, enclosures around drilling sites (or the delineation of borders) are largely enforced by ancient technologies: fences and walls. At sea, one cannot demarcate or even hope to enforce space in the same way as the land, even in our modern era of drone surveillance and high-tech naval radar. Only when these infrastructures marry the sea to the shore – with pipelines, submarine cables, and loading terminals – does the incongruency between land and sea seem clearest. To make matters worse for states (and better for fishermen), enforcement itself is a haphazard enterprise: a combination of coast guards, naval vessels, private contractors, and police are all tasked with catching transgressors, although, in the absence of fisheries-specific enforcement fleets, many fishermen manage to fly under the radar. While expatriate fishermen are often summarily deported upon infraction, nationals are often shown leniency (unless, of course, they are captured by another country’s enforcers, which has led to diplomatic tussles between the littoral states).

Figure 3: A submarine cable extends outward to sea from a beach in Abu Dhabi’s Al Dhafra region (Author photo, 2024)

Figure 3: A submarine cable extends outward to sea from a beach in Abu Dhabi’s Al Dhafra region (Author photo, 2024)

Despite the significant changes in property regimes, society and environment in this region over the last century, spending time with artisanal fishermen today largely reveals the ways in which the story of fishing in the Gulf is one of continuity rather than change. Most fishermen from Oman and the U.A.E. still fish in the manner that their ancestors did, using handlines and castnets. They also mostly fish where their forefathers did, envisioning the sea un-enclosable commons rather than a series of enclosed, private property regimes.

Figure 4: A fishermen brings a giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis) on a handline (visible in the left foreground) in the Persian Gulf (Author photo, 2024)

Figure 4: A fishermen brings a giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis) on a handline (visible in the left foreground) in the Persian Gulf (Author photo, 2024)

One of the more remarkable phenomena I’ve observed in the course of my ethnographic work is the various solidarities between fishermen at sea, for whom being an artisanal fisher is often a more relevant category than nationality, tribe, or ethnic group. Geopolitical antagonisms that dominate the news cycle are often overlooked (if not ignored) at sea between artisanal fishermen. The ire of these men is instead often directed toward industrial fishers of all nations – including the tuna and sardine fleets of Pakistan, India, Iran, and occasionally China at the outer reaches of the Gulf of Oman – who all reap unimaginable quantities of fish from the sea. Fishermen, in turn, also offer critiques of the states they see as inadequately protecting their marine environments from these foreign incursions. The Persian Gulf, as a region, is well-suited for these artisanal solidarities. This sea – which has been crossed so many times by so many people, which has witness families from both shores live and settle on opposite coasts for generations at a time – has only recently hardened into the national divisions of today.

To fish in the Persian Gulf as it if were still a commons, rather than a palimpsest of enclosed, exclusionary, proprietary spaces reinscribes the “high seas” character that prevailed in these waters before the oil era. We would do well to pay closer attention to fishermen as they enact their own vision of the sea, their own ideas of a natural right to the ocean, and their own forms of activism as they confront the governments that claim to be their patrons. In Oman (and to a lesser extent, the U.A.E.) fishermen have pegged the state as being responsible for collapsing fish stocks. They openly blame the relevant ministries for their lack of enforcement, for inadequate regulation, and for halfhearted environmental protections. These and other claims are notable, in part because political activity is often met with harsh reprisals in the Arab states of the Gulf.

But fishermen here and elsewhere are right to be worried about the increasing environmental changes, even if many of them buck regimes of enclosure. Overfishing especially threatens the few unenclosed strips of the sea where fishermen are free to fish as they please. A degree or two change in sea surface temperature on top of this means that already overfished species might yet alter their behavior when breeding or migrating, even among some of the most heat-tolerant marine species on earth. This portends less and smaller fish in fishermen’s nets, something which people have observed here and elsewhere around the world.

Why should oil companies get to reap vast quantities of fossil fuel from beneath the sea, materially altering the seascape, damaging the seabed’s fragile ecology, and tampering with the climate, all at the exclusion of fishermen? When will states understand that national wealth includes the riches of the sea in addition to fossil fuels? Who will look after fishermen when there are no fish left? Who, other than God, can possibly “own” the sea?

Comments are closed.