Cultural Revolution in Iran and Targeting the Political Rivals

Interview with Mehrak Kamali

August 1, 2024

Reading Time: 22 minutes

In late 1990s, the monthly journal, Lawh, launched by Mohammad Ghaed, started a series of interviews with Islamic intellectuals and patrons of the 1980 Cultural Revolution (CR) and you did some of these interviews. Why did Ghaed and you decide to go back to this bitter incident and delve into it? was it something you personally experience it? Were you a student at the time?

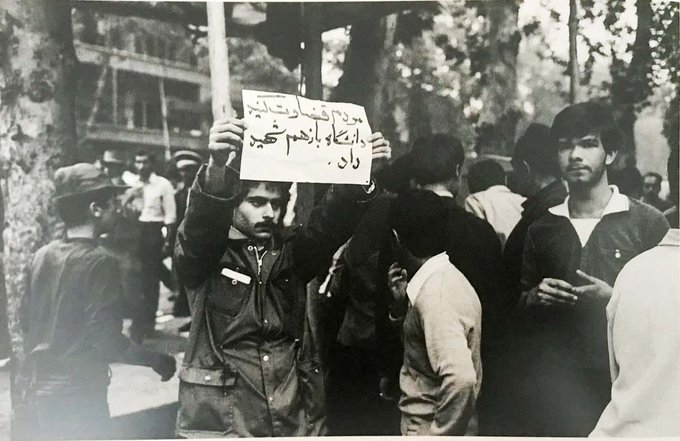

I was interested in the CR for both intellectual and personal reasons. I was one of the young people who opposed the incident when it occurred. I recall the first day of the CR, the 20th of April 1980, I heard the news when I was in front of the Shiraz University School of Medicine. The same day afternoon, I was in a march with my student friends in front of the Faculty of Literature. I was only fourteen years old at that time. We were clapping our hands in air and chanted, “Unity, Struggle, Victory.”

Hezbollahi groups took over both faculties in the following day, and a fight had erupted between Komitehchi-ha and the revolutionary guards (IRGS) and the students. The protests spred out from university to the Ashayer-e Shiraz High School, which was close to the university and the streets surrounding them. The stones that hezbollahi group threw at me at the Paramount Intersection that afternoon hurt me. I was stunned when a stone struck the back of my ear. Houshang Mohebpour found me as I was running and sobbing from the deadly chaos, and he took me to the hospital. My elder comrade, Houshang, was executed by the Islamic Republic’s murders in 1982. I was brought home by Houshang late at night, after they had bandaged the back of my ear. Standing in front of the door were my anxious parents. All night long, I wavered between pain and numbness, sleep, and wakefulness. My right side of the face was like a pillow when I woke up. I wore my clothes to go out; my heart was in the street.

Not only was I hurt that day, but I also saw friends being imprisoned, banished, even killed. Later on, I became a victim of the CR because I was not allowed to enter the university due to the new admissions (gozinesh) policies. Despite taking multiple entrance exams, I was turned down in the interview process. I was finally admitted to an undergraduate program in 1996, following the cancellation of the gozinesh interview. My classmates were 13 years younger than me when I was finally become a university student.

My interest in studying the CR was also motivated by academic factors; we released a research report regarding the detachment of medical education from the Ministry of Higher Education and its affiliation with the Ministry of Health in the second issue of Lawh.

My research for that report revealed that the policy had its roots in the CR. I examined the details of the parliamentary discussions on the topic and spoke with Iraj Fazeli, Minister of Higher Education in 1985, as well as Mohsen Saghaei, the former dean of the School of Medicine at University of Tehran, and neurosurgeon Khosro Parsa, both criticizing the policy. According to Parsa, the policy’s objective was to weaken doctors’ social and political influence by making them more dependent on the government, displacing competent medical professionals, and turning them to government employees. I learned from these interviews that undermining the authority of experts was a crucial objective of the CR. After talking with Ghaed about the report, we concluded that a more thorough investigation into the CR is necessary.

Both a victim and witness to the CR in 1980, and a university student in 1990s, you have carried the CR for two decades. Tell us how did you start working with Lawh and Mohammd Ghaed?

In 1998, I had multiple articles published in a popular journal then named Jame-e Salem. In a meeting with the late Firouz Guran, the journal’s chief editor, he told me he has an offer for me if I am going to work more seriously as a journalist. I asked him about the offer and got excited. When he mentioned that Mohammad Ghaed has obtained a permit for a monthly journal on education and is looking for an assistance. I knew Ghaed as a top journalist who served on the editorial board of the Ayandegan newspaper during the revolution, also working with Ahmad Shamlou on Ketab-e Jomeh and above all, I was captivated with his flawless translation of William Worden’s Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy. Guran introduced me to Ghaed and I began working with Lawh the following week and became his primary assistant. I learned a lot from him and from Hossein Shahidi, the media researcher and professor of communication sciences, who visited Iran in the fall of 1998 and at Ghaed’s request, set up a one-week training shop for Lawh employees who didn’t have a systematic study on journalism. Our instructors included Guran, Hassan Namakdoust (deputy editor of Payam-e Emrooz journal), the late Mehdi Farahmand, an experienced journalist and the chief editor of Ettela’at newspaper during the revolution if my memory serves me correctly, and Ali Zarghani, the founder and managing director of Snaat-e Haml-o Naghl (The Industry of Transportation) journal.

How the CR was chosen as a report theme at Lawh?

Lawh’s content was all about the education in Iran. Like I mentioned earlier, Ghaed’s decision to explore the CR was influenced by the separation of medical education from the Ministry of Higher Education, in 1985 and we had to go back to the 1980 to explore the CR. The society was eager for the truth too, and this prompted the creation of the first comprehensive independent report on the CR in Iran, which was published in multiple editions of Lawh. Gholamreza Masoumi and I collaborated on the research and interviews up to the fourth issue, after which I continued solo under Ghaed’s supervision.

With this series of reports, we aimed to slake the new generation’s thirst for information about the actualities of the CR—a thirst that became increasingly apparent following Mohammad Khatami’s presidency in 1997 and the press’s blossoming. Ghaed believed that our society is dealing with historical ruptures and kind of battle between different subcultures; research on CR could address both of them. I recall his paper titled “Black Hens, White Hens: Double-yolk eggs” would argue that our cultural environment is constantly changing, akin to shifting sands where even mighty rivers can be obscured, not to mention a small stream.[1]

I think his argument would reveal the nature of CR discourse, as Khomeini’s and his followers were seeking to create two types of ruptures: First, to integrate the university into political Islam project by disrupting its research and teaching routines and regular processes. Second, to isolate leftist and secular theoretical viewpoints and eliminate those who hold them in order to win the battle of subcultures. The CR, in my view, was an extension of the November 1979 US embassy takeover by students identified as the Imam’s Line Student Followers. In line with this model, people take initiative and act out of a sense of duty and commitment, achieving objectives that the government initially wants to achieve but is reluctant to own up to. The seizure of the embassy theoretically neutralized the rival anti-imperialist leftists and secular forces, and the CR physically destroyed them. Although the project to Islamize universities was visible on the surface, it was really just a political ploy with a strong desire to suppress the political movement in the universities. This is not just my view; in interviews I did on behalf of Lawh with Muhammad Maleki, Sadeq Zibakalam, and Morteza Mardiha, all three agreed with me that the main objective of the CR was to remove strong political opponents and engaged students.

What did you find about the scope of university purges in your interviews?

The first report was published in February 1999, in the 3rd issue and continued up until the 8th issue in June 2000. These reports drew on interviews as well as archival research. According to what the Cultural Revolution Headquarter (CRH) authorities said, their primary aim in the period 1980–1984 was to pinpoint academics who did not align with the government. Their approach was naive. In an interview with the Daneshgah-e Enqelab journal in 1981, Abdolkarim Soroush has explained they listed the characteristics of the future Islamic university based on a list of fifty drawbacks of existing universities. He suggested that planning committees were proceeding like blind people: “We lit a lantern to move forward, then we would pause to think about the next step and continued like this…”[2] Such naive approach to the university was the basis of eliminating the rival theoretical and political groups and framing the future of university. They had no concern for academic freedom, long-term planning, or critical thinking.

Soroush told us they would select the professors based on their “commitment” and tazkyeh and personal histories, individual characters, and beliefs of the faculty would be examined to assess their commitment. Non-Islamists were not entrusted, even if they had the expertise. He explains they follow the CRH criteria and would check to see if professor “has the piety, gives priority to tazkyeh over expertise, if could combine the faith with the knowledge, if does seek knowledge without obtaining a revenue…”. Later on, Tarbiat Modares University was founded as a result of this worldview. Practically speaking, this university trained the less dedicated professors who were in charge of training future professors who would instruct students.[3]

Gholamreza Masoumi conducted the first interview, which was published in April 1999, with Gholamabbas Tavassoli, a professor of sociology at the University of Tehran. Following the closure of the universities in May 1980, Tavassoli began serving as the head of the humanities planning committee at the CRH. The seminary clergies in Qom insisted on leading the committee, claiming they had ideas. According to Tavassoli “to review the content of the university programs, they formed a committee comprising a few seminarians and university professors.”[4] He was excluded from the system at the time because he belonged to the Nehzat-e Azadi party and was seen as having a Western outlook. Even though Tavassoli had a different political affiliation, he worked with other Islamists to eliminate leftists and secular academics. The university’s independence did not worry him at the time, as he was fascinated by the chance to create an “Islamic social sciences.”

Did you find anything new about the students that were suspended and expelled?

We published a part of Towfiq Gholizadeh’s article about the statistics of students who were suspended and expelled during the CR; it revealed that over 57,000 students had either of these situations. The matter is obvious: there were more than 174,000 students enrolled in the university during the 1980–1981 academic year, the year the universities were closed, and when they reopened in 1983–1982 academic year, the number declined to 117,000 registered students. This indicates that 57,000 students vanished from the universities.[5] Universities were an example and representation of Iran’s political society back then.

Did you interview Islamic professors as well? How did they describe the goals of the CR?

My interview with Sadeq Zibakalam was published under the heading of “I officially and publicly ask for halaleyat (religious pardon).” Zibakalam acknowledged that producing Islamic social science, the core of the CR project, was based on destroying academic freedom. He told us that in 1981 nobody dared to ask Dr. Tavassoli what the Islamic sociology is; if you claimed then there is not such thing as Islamic sociology, Soroush and many others would put pressure on you. He added, of course, then he believed himself that the management science that works for Iran is different from the management science that works in the US. However, he found this notion the most ludicrous and unscientific of all later on. However, when Soroush, Tavassoli, and Zibakalam arrive such conclusion, thousands of people were expelled from universities, imprisoned, and put to death by their like-minded colleagues in the security apparatus. Many scholars left the country. The CRH’s university programming contributed to the demise of social science, the erosion of academic freedom and independence, and the establishment of superstitious beliefs and ideologies as the dominant forces in higher education. I interviewed Abdolkarim Soroush with many detailed questions, which was published in Lawh, sixth issue. We also republished his 1981 interview with the journal of Daneshgah-e Enqelab, in which he expressed his support for the Islamization of the universities. Eighteen years later, he attempted, in his own unique language, to respond to my questions and justify his previous support in a rather mechanical manner: “…the only way to build an Islamic humanities if it be feasible at all, is through collective work of a group of people who adhere to Islamic principles, to produce a new knowledge rather than repeating existing theories). Their outlook will naturally be reflected in their scientific production, and over a few generations, it may be possible to produce humanities that bear Islamic thoughts.” In 1981, when he supported the CR, his wording was not “may be” or “possible.” Then, it was a duty to promote the Islamization of the universities, which was finally achieved by force and through eliminating other ideologies.

Back then he would say: “Universities should embrace the scent of Islamic thought all over; this will make our garden fragrant for everyone who enters it seeking knowledge, and they immediately smell its delightful scent.” I believe, the main preoccupation of the CR theoreticians like Soroush and Tavassoli, and its operators such as Morteza Mardiha and Vahid Ahmadi was to consolidate the government and suppress political opponents, rather than creating a “delightful scent” at universities and imposing it Iranian academics. The interview with Tehran University’s president at the time of the CR, Muhammad Maleki, was published in the journal’s seventh issue.

He named the 1980 incidents a “cultural coup” rather than a “cultural revolution.” He gave the subject its exact historical background and contextualization, and by narrating the events in chronological order, explained the challenges faced by universities from the early days of the revolution until the end of the CR. He believed that all government factions, from Khomeini and the Islamic Republican Party to Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan and President Abolhasan Banisadr, were irritated by the university, which served as the primary base for leftist and secular forces. All factions in power or seeking power within the Islamic Republic would benefit from excluding the universities from the political arena. Even the Mujahedin-e Khalq organization, which still aspired to be part of the political system, remained neutral at the outset of the CR and did not object the university’s closure.

Did Maleki discuss the number of expelled faculty members at the University of Tehran during his presidency? It has been reported that seven hundred faculty members were purged from the university during his tenure. Did you know anything about this?

No, he didn’t say anything about it. I also had no information about this issue then, and I hadn’t followed the events of the revolution’s early days.

In the interview, Maleki notes that he believed Bazargan and the Revolutionary Council were the ones who first proposed closing universities prior to the CR because they believed that the government would face difficulties as a result of the diverse opinions of the students. It’s interesting to note that the Bazargan was only a member of the Revolutionary Council at the time, having resigned as prime minister. How much of an impact do you believe people like Bazargan have had on this project?

It is not absurd that Bazargan would support dismissing faculty and students who hold left-leaning opinions, but I have no doubt that the CR project was designed elsewhere, out of sight of Bazargan and his allies. The imprints of Imam Line Student Followers in the CR are much easier to follow than those of the so-called liberals back then. Of course, neither the liberals nor the Mujahideen Organization were not concerned about the elimination of their left-leaning rivals and did not take a practical stance against the CR.

According to recently released documents, which include the materials published by Maleki in his 1980 book, University of Tehran and the Footsteps of American Imperialism, the purging of university professors appears to have followed the purging of other government employees and began prior to the creation of the CRH. It was authorized by Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleghani as well as the University of Tehran Board of Trustees, with Hashem Sabaghian and Maleki as its members. Apparently, the CRH even opposed it, which led to a strong reaction from the University of Tehran Board of Trustees. Considering Maleki’s interview, what is your opinion on this?

If you mean the purges in the early days of the 1979 Revolution, there was no CRH to be in favour of or opposed to it. Maleki depicted the atmosphere of the University of Tehran after the Revolution in the interview. he did not refer to the purges in the early months after the revolution. I do not find it strange that the University of Tehran Board of Trustees approved and encouraged the expulsion of academics connected to the Shah’s administration, given the anti-monarchy climate of the time. It’s interesting to note that Ali Shariatmadari, the Minister of Science and Higher Education at the time, argued that judges should hear cases involving individual professors and make decisions regarding their removal; however, his suggestion was not followed.

During the CR, individuals like Hassan Habibi (the spokesman of the Revolutionary Council) and those gathered in the Daneshgah-e Enqelab journal pursued an exceptionally harsh approach toward the university and its students; it seems they intended to undermine the university fundamentally! In an interview back in 1979, Habibi says that he would shut down the Ministry of Science if he had the power. Of course, they have a more balanced approach when giving interview to Lawh, particularly those members of the CRH. Such approaches by the so-called liberal members of the government problematize the assumption that a radical/moderate dichotomy actually existed during the CR.

I’ll read you a passage from our report to start off my response:

Beginning in the first year of the Revolution, a tradition was formed that endures to this day: groups that appear to be outside the government but are initially its sincere and passionate followers launch an initiative which is quickly acknowledged and takes on legal status. In the CR case, when the gap between Banisadr and his opponents was deepening day by day, the university closure was one of the rare issues that both sides advocated, and they quickly reached an agreement.

During the CR, all government factions did not oppose the purge of the leftist professors and students from the universities, this included the Mujahideen Organisation, and the Tudeh Party. Among the Marxist groups, the pro Tudeh Party students were among the first groups to follow the decree to evacuate their offices at universities. They refrained from confronting the government. So, the CR led to the removal of diverse groups from the university. Within the government, there was a dual hardline-moderate approach, but it worked at individual level and was based on individual tastes, not a severe ideological gap.

Universities and Kurdistan province were two powerhouses of the left, and both of them were under attack in April 1980. The practical leadership of the CR was in the hands of zealous students who had plotted to participate in power and were definitely in contact with powerful groups such as the Islamic Republican Party. Those who remember those years know that a large tent called the “Tent of Unity” was set up in front of the main gate of the University of Tehran, which was the base of the Hezbollah, who were organised by the Islamic Republican Party and attacked the supporters of other political groups and book stalls. The connection between these groups and the Islamic Association of Students was not overt. It was rumoured that the name “Office of Consolidation of Unity” (The Centre of Islamic Student Associations) came from this process.

Morteza Mardiha admitted in an interview with Lawh the cooperation and organisation of Islamic Republic supporters from outside the university, with Muslim students loyal to Khomeini inside the university. In his interview, he says he participated in the CR while not being a university student, “freely” engaging in political activities and “informally” working with friends. “Free” and “informal” in the context of that time have no meaning other than the cooperation of people like him outside the university with the students defending the CR inside the university. He came from Isfahan to Tehran and stayed in the dormitory of Amir Kabir University to be able to participate in the raids of the Hezbollah against their rivals.

Jalal al-Din Farsi and Hassan Ayat are frequently mentioned in your interviews. For example, Maleki suggests that these two are responsible for the CR move. Did you find more evidence support these two had an important role to play in this process?

No, unfortunately. I don’t know more than what has been mentioned in Maleki and Vahid Ahmadi’s interviews. My last interview was with Morteza Mardiha and Ahmadi, two other activists of the CR. Mardiha argued that the move was a mistake, while Ahmadi was still supportive of the project. Unlike Tavassoli, Soroush, and Maleki, Vahid Ahmadi did not consider the “Islamization of the university” as part of the IR goals. He argued that the CR aimed to align the university with the revolution, and the current concept of Islamization of the universities was not much a discussion back then. In response to another question about the oppressive nature of the CR, he said:

…too much freedom had created a fear of risk; many were thinking what would happen if we could not control the situation. Actually, there was no way to control it. Various groups that existed were untrained; they desired to undermine the system… the pro-revolution figures felt threatened.

Ahmadi’s account is slightly different from the others. To him, the students’ initiative made the essence of the CR. He constantly refers to “us” as the ones who drive the project. He portrays the incident as a self-motivated and popular movement borne out of a sense of responsibility rather than a politically and provocatively motivated project by the state. The CRC has been the ultimate decision-maker only in selecting the professors. He holds Banisadr responsible for the political purges, because he set a deadline for the evacuation of the students offices. What is your opinion on the dichotomy of the hardline students and the CRC and, of course, Banisadr’s role in this?

Vahid Ahmadi is an example of the people I mentioned earlier: the students who believed that they, Daneshjoyan-e Khat-e Imam (The Imam’s Line Student Followers) have the right to eliminate the others because they were part of political system. They called for CR because they knew they would not succeed to win the students committees in a healthy competition. I believe, this claim that student agency in the CR was independent from the government is a myth. They were acting in coordination with the visible and hidden centres of power. Just check the news published in the Jomhoori Eslami newspaper; there are many news on the IRGC’s interventions at campuses in support of Islamic students. It occured at the University of Tabriz on the very first day of 1980, and marched to the campus to help them.

Khomeini issued the order for the CR in his 1980 Nowruz message. He said: “A fundamental revolution must take place in all universities throughout Iran so that the professors who are in contact with the East or the West are purged, and the university becomes a healthy environment for teaching Islamic sciences.” As Ahmadi confirms, these students had consulted with Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri and Hojatoleslam Mohammad Javad Bahonar before they occupy the universities. With Khomeini’s mandate and the consultations, they had with other leaders of the government, they put the groundwork to occupy the University of Tabriz and Elm-o-Sanat University in Tehran in mid-March 1980. We know this was ignited in Tabriz, when the dialogue between different groups of students turned to fight in Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s speech, and hezbolhi students (pro-government students) attacked the offices of other groups of political students. We know that Hassan Habibi, the Minister of Science and Higher Education at the time, immediately demanded the evacuation of the universities and even opposed to give the political groups the three-day deadline. All evidence negates the project being a student-initiated and independent move. We have published the related detailed information on these issues in the third and fifth issues of Lawh.

Ahmadi claims that the CR process was influenced by and was a continuation of the occupation of the American embassy. What do you think about the relationship between the CR and the embassy takeover?

Ahmadi claims they were inspired by the US embassy takeover, and I think that is a truth. But he sees it a positive inspiration, while I see it harmful. The hezbolahi students (pro-government students) and their powerful allies approached the university as a centre of cultural conspiracy against regime, as the US embassy was regarded as the centre of political conspiracy. The occupation of the embassy was an initiative which politically disarmed the leftist groups who wanted to be the champion of the anti-American struggle, now they were ready to repeat it at the university and entrench their power there by expelling the leftist groups and independent academics.

Even Ahmadi mentions about the confrontations with professors as harsh in some of the provincial universities. Have you found any information or reports about these incidents?

We found some reports on University of Gilan, Sistan and Baluchestan University, Shiraz University, and Jundishapur University in Ahvaz. The most severe crackdowns occurred at Jundishapur University. At least 12 people were killed at Jundishapur University during the CR, according to news. Furthermore, 6 people were sentenced to death and executed for participating in the university clashes, after a few-hour trial, on April 12, 1980. In Shiraz, where I was injured in demonstrations against the CR, one student was killed and many injured.

In almost all of the interviews you did at Lawh, the Islamic intellectuals you interviewed argue that educational planning was the priority of the CRH and issues related to university management came second. They claim that the Islamization and purging project were initiated by a radical group who replaced the CRH in 1984 and formed the Cultural Revolution Council (CRC). What are the impacts of the CRC on the processes of the CR?

No doubt the dismissals were officially announced when the universities were reopened in 1983. However, the heterodox students and academics were aware of the pressures to remove them from the universities right after the April 1979. As our interviews and research show, the members of the CRH and the CRC were all agreed on two issues: the purging of universities and promoting the seminary education. They believed the seminary education is a utopian model that universities had to adhere to.

All our interviewees, even Maleki, had supported the idea of building a higher education based on the research and debate training methods of the seminaries. The humanities were regarded the cause of credentialism, youth intellectual corruption, their distancing from religious beliefs, and attitude toward the West. In these same interviews, Ahmadi considers the fight against credentialism to be one of the main goals of the CR and refers to the advantage of seminaries in this regard; let’s pass over the fact that government officials themselves later had a thirst for obtaining credentials and showing they enjoy the “PhD” titles.

Soroush said in our interview that he never believed in Islamic humanities. Yet, he had said, “Universities must fully embrace the fragrance of Islamic thought” when he was the spokesman for the CRC. Tavassoli was the head of the humanities planning committee at the CRC, and he founded the “Seminary and University Committee” which supposed “to bring professors and the seminarians together to examine the content of the [humanities] disciplines.” They either believed in the seminary system advantaged or felt it a necessary move to collaborate with the ruling clerics to suppress and destroy their political rivals, mainly leftist groups.

Heading towards a utopian seminary system jeopardised the secular university education in Iran. We became interested to compare the education process at the seminary schools and universities. Our comparative research on teaching methods, the exam design, and the teacher-student relationship at both institutes revealed that universities are mimicking the seminary schools’ methods, and it serves its collapse. We published the report in Lawh’s seventh issue in December 1999.

Did you try to explore how parties and political organisations reacted to the CR back then? It seems that you missed/excluded that part in your reports.

Unfortunately, that is correct. I could remember how some of them reacted to the issue and could have found some of their statements issued back then. But you are right; we missed this section in our reports. It was good if we had also reflected the voices of the victims of the CR, but we did not. Others should complete this narration and fill in the gaps.

When you were putting these reports together at Lawh, the famous student protest occurred at the University of Tehran dormitory on July 9th 1999. Did the incident have any impact on your interviews and the content of the reports?

In the sixth issue of the Lawh, we had a detailed roundtable discussion with the students who were directly involved in the July 9th protests. The roundtable was published in two parts and carries the titles of “Who Lit the Match and Why?” and “Reflections on What Happened.” It was a coincidence that my interview with Soroush was published in the same issue, and it was titled “In the End, They Didn’t Know Where the Intended Destination Was.” The coincidence made many readers compare the two incidents. 19 years after the CR, students stood against government oppression at universities, and did not tolerate injustice. Among our interviewees, only Vahid Ahmadi compared the two incidents to confirm his judgment about the self-motivated nature of the CR. He referred to the July 9th protests as another example of a self-motivated movement, which was a wrong comparison to me.

The July 9th student protests were self-motivated, and they were attacked by the vigilantes (Lebas Shakhsi-ha) alongside security and police forces. I was residing in the university dormitory then and saw that the whole story began with the distribution of handwritten leaflets by a few students. The Muslim students occupying the universities on the wake of CR could be compared to the organized attacks of the vigilantes to the dormitory on July 9, 1999.

In assessing the products of the Islamization project, Tavassoli and Soroush comments that only five volumes of books were compiled, after so many meetings were held at the CRH and joint work with the Society of Seminary Teachers of Qom. Looking into the regulations approved by the CRH in 1983, it seems the existing curriculum did not change much; only some general courses (including Islamic Knowledge, Arabic, and some other courses) were added. If it is true, what was their actual achievement? Looking at reports you put together 23 years ago, how this project could be assessed?

Two separate but related results could be drawn from our reports about the CR and the CRH (and later the SCCR). The CR was a continuation to the occupation of the American Embassy and was a prelude to subsequent crackdowns. This move did not have a goal other than expelling the militants from the universities. When hezbollahi groups, were hitting the other students, while Islamic Revolution Committees (Komiteh) and the IRGC supporting them, they were not trying to Islamize the universities. they aimed to restrict the secular leftists and communists. The CRHs were the product of this sinister goal setting. However, they carved out a function for themselves: they reorganize the body of university to deprive it from its independence and academic freedoms, and they did it under the pretext of promoting Islamic knowledge. They inspired the seminary system and tried to refabricate the humanities in the style of seminaries. The result was destruction and decline. The policy was carried under the rubric of Islamization of the universities, but building a compliant and powerless university was at the core of the project. They largely succeeded because they created a passive university that remained silent until 1997 and the emergence of the reform movement.

Thank you for participating in this interview.

Endnotes

[1] Qaed, M. 1999. Lawh Educational Monthly, 5: 20.

[2] Soroush, Abdul Karim. 1998/1377. Interview with Daneshgah-e Enqelab Monthly, 3 and 4, 1998, quoted from Lawh Monthly, 3: 26 and 28.

[3] Ibid. Grading the professors at the CRH, Lawh Monthly, 4: 31-32. April 1378

[4] Masoumi, Gholamreza, 1999/1378. Interview with Gholamabbas Tavassoli, CRH: Revising Academic Programs, Lawh Monthly, 4.

[5] Gholizadeh, Towfiq ,1999/1378. A Sketch of the historical process of education and the role of the state, republished partially under the title: Closing and reopening of the universities, Lawh Monthly, 7: 56.

Comments are closed.