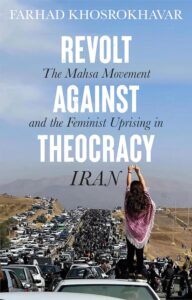

/Book Review | Reading Time: 13 minutes

Revolt Against Theocracy

The Mahsa Movement and the Feminist Uprising in Iran

Saeed Paivandi | December 15, 2024

© Background Photo by Leila Araghi

ISSN 2818-9434

Revolt Against Theocracy is the latest book by Farhad Khosrokhavar, a sociologist and university professor in France, about one of the most important collective protest actions of recent decades. The book is an analytical sociological and anthropological narrative of the Women, Life, Freedom Movement (or Mahsa Movement), which can be referred to as a protest action and a comprehensive movement as well as a profound cultural revolution. The author’s goal is to reinterpret this socio-political event and show its mental and ontological aspects as well as its main characteristics, especially in relation to women and its emphasis on the joy of living and the negation of the death-ridden and mournful culture of the government. The introduction of the book refers to the new subjectivity of young people who challenge the culture, the dominant discourse, and the values of the Theocratic government. The central role of young girls and women in this movement, according to the author, is a response to the government’s gendered and discriminatory policies that marginalize half of society with a traditional, religious understanding of women’s role and status. The main consequence of government policies that view women more as symbols of fertility and reproduction is their disappearance, structural gender discrimination or de-genderization, and the denial of sexuality in the public sphere. From the author’s perspective, for the first time in Iranian history and perhaps in the region, women and their demands were at the center of the dynamics of a popular and comprehensive protest action.

The book consists of 6 parts. The first and third parts of the book deal with the main characteristics of the Mahsa movement and the role, demands, and actions of women and the younger generation. The second part examines the Mahsa movement in the context of Iranian society, including in relation to two important movements of the 1390s (2010s), namely the widespread protest actions of 1396 and 1398. The fourth section is a return to some important figures and the characteristics and life paths of the “new intellectuals,” among whom women make up a significant part. The fifth and sixth sections refer to the major structural shifts in contemporary Iranian society that have become increasingly prominent in the last two decades.

The existential phenomenon of the joy of living of young people

Among the main discussions raised in the book, it should be noted the meaning and reason for the prominence of the joy of living phenomenon (“joie de vivre”) in the face of the government’s culture of sadness and death-glorification, which is examined especially in the first part (pp. 5-69) and also occupies the most pages of the text. The author highlights the main feature of the Mahsa movement by highlighting the “joy of life” in the slogan of « Woman, Life, Freedom » in the face of a government that tirelessly praises death and the everyday life of mourning, relying on religious rituals and ceremonies. The book considers the joy of living as an ontological need and experience of the young generation to negate the discourse of death-ridden culture of the government, based on mourning and sorrow. The slogan of Woman, Life, Freedom contains two messages regarding the issue of joy of living: the first message is related to existential individual freedom and the second message contains collective freedom (democracy).

The author returns to the roots of this cultural tension in Iranian society since 1979 and the various ways in which the government’s death-stricken culture of grief and mourning was formed. The government that emerged from the 1979 revolution transformed mourning, martyrdom, and death into symbols of the new political order. To trace the cultural genealogy in which the religious government was the main actor after 1979, the author points to the difference between the culture of mourning in the Shiite tradition, especially since the Safavid era, the rise of Shiism as the official religion of the country, and the post-revolutionary culture of grief and sorrow, whose main hero was the martyr for the Islamic state based on political Islam. Revolutionary death and martyrdom in the eyes of Islamists in power are the central themes of Farhad Khosrokhavar’s two previous books, “Islamism and Death” and “Anthropology of the Iranian Revolution,” in French[1].

In traditional Shiite culture, mourning in public mourning ceremonies, especially in relation to the third Imam, was more of an expression of sympathy and collective guilt in the face of an event such as the massacre of Karbala in 59 AH (680 AD). The main function of mourning and crying and wailing for the third Imam or other figures of early Islam over the centuries was considered spiritual relief and purification, and a kind of Shiite “catharsis” in the context of the historical experiences of Iranian society.

An important turning point that occurred with the 1979 revolution in Iran was the transformation of the culture of grief and mourning into a culture of sorrow and heroic martyrdom in the newly emerging theocratic state. People like Ali Shariati played a key role in shaping this culture in the 1970s. Shariati was the theorist of martyrdom, its praise and sanctification in the revolutionary narrative and in the service of the political struggle against the secular and class based government in consonance with a Marxist ideology, which was also widely welcomed by the youth at that time. A genuine Shiite is a revolutionary in his view, is someone who is ready to suffer, sacrifice his life, and be martyred for the sake of revolutionary ideals. For Shariati, genuine religiosity was crystallized in the negation of life in a non-religious class-based society and the acceptance of the sacred death. By promoting a culture of grief and sorrow or martyrdom, the religious government introduced a new interpretation of mourning and martyrdom in Shiite tradition based on the sacrifice of Imam Hussein, which formed the basis of the Theocratic government’s post-revolutionary discourse.

The revolutionary movement in 1979 and the Islamic regime that emerged from it attempted to turn enjoying life in a secular manner during the Pahlavi regime into a guilt feeling, and put the sacrifice for the sake of revolution as the top values of life. Thus, suffering and sacrificing oneself for the sake of the Islamic Revolution as the major values of life became paramount and antagonistic towards the secular enjoyment of life during the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah. The propaganda discourse of the theocratic government during this period, using war conditions and political repression, sought to impose a deep feeling of guilt for happiness and enjoyment of life through the body as immoral. In this way, the Islamic government transformed the figure of the martyr and the traditional mourning rituals and ceremonies into the symbol of its cultural identity. It was as if an unwritten contract and a kind of political give-and-take were created between the Islamic Republic and a large part of men. The theocratic government traded the continuation of male dominance, support for “male honor,” and control of women’s bodies by men in exchange for its political dominance on men and society in general.

The transformation of traditional culture and its instrumentalization in society through the politicization of martyrdom, although it enjoyed a certain acceptance among a group of traditionalists and radical Islamists alongside the government, gradually created a deep divide between large segments of society, especially the youth on the issue of living happily and giving importance to the secular culture such as music, dance and other branches of art, entertainment and sports. For the government, showing the body, especially for women, in the public sphere means challenging the authority of the religious order. The government’s goal was to push happiness into the private sphere, to shape the public sphere devoid of happiness and individuality, in order to completely dominate the body, especially women’s body, and impose a death-centered culture to justify its legitimacy. In this way, domination of the body and control of sexuality became an important political goal. The Mahsa Movement highlighted this deep cultural divide. Collective happiness in the public sphere was a sign of freedom and self-assertion, a mockery of the government and its value system. The joy that emerged in the Mahsa movement was for freedom and collective protest against the culture of mourning, sorrow and grief of the theocratic government and its prominent characteristic was its secular nature. Women showed off the joy of life in the streets with greater enthusiasm, dancing hand in hand with men, throwing their headscarves into fire and displaying a new citizenship in which the autonomous body was the epitome of individual female freedom encompassing the male freedom by mingling with men. The Mahsa movement was a kind of open declaration of war on the theocracy, which, having failed to provide for material needs and manage the economy, society and environment, had turned to the symbolic realm to display its religious authority. In the discussion about the joy of living and the negation of the state’s mourning culture, F. Khosrokhavar devotes a special place to the issue of the body and corporeality in the Mahsa movement. Joy of living in the Mahsa movement meant, among other things, liberation from the constraints that the government imposed on society in relation to the body. It was as if removing the veil and throwing compulsory headscarves into the fire in a collective celebration was liberation from the heavy burden that the government had forcibly placed on the shoulders of women in society. The politicized female body became an object of liberation and affirmation, and the demand for its liberation was accompanied by the demand for political freedom. For the first time in a Muslim society, the book sees women’s bodies not as a screen to defend men’s honor and exclusive sexual pleasure, which had to remain hidden from the public eye, but as a battleground for the political freedom of women as well as men. Khosrokhavar speaks of a profound metamorphosis in the meaning of citizenship through female citizens who demonstrated the will to be free first and foremost through their bodies. New gender relations were shaped within this transformation in political citizenship. Women and men thus stood side by side in the struggle for political freedom.

Mahsa Movement as the First Inclusive Women’s Movement

Another main argument of the book is the description and analysis of the Mahsa Movement as the first inclusive women’s movement. The author does not mean to negate previous feminist movements in Iran by making such an important statement. From the book’s perspective, the Mahsa Movement should be considered the antithesis of the Islamic side of the 1979 Revolution. This time, women’s participation did not take place as wives, mothers, sisters, or daughters of men, but as autonomous protesting and demanding citizens. Mahsa and the very young girls who initiated the protest actions played the real and symbolic role of female citizens who came out in open opposition to gender discrimination, the status quo, and the political system in general. In the author’s words, the Mahsa Movement, in its endogenous dynamic process, became an inclusive feminist project at the level of Iranian society and in direct confrontation with a government that was dominated by a gendered and patriarchal culture and politics. For this reason, before addressing the indicators and signs that lend credence to this important proposition, the book deals with movements and protest actions before 1401 (2022) (Part II, pp. 60-84). The author shows that feminist movements against various forms of discrimination or individual protests against compulsory hijab have a kind of historical continuity. The discussion is about how actions that intended to reduce discrimination and unequal laws against women, such as the One Million Signatures Campaign, gradually turned to fighting compulsory hijab. F. Khosrokhavar believes that the One Million Signatures Campaign for Legal Equality in 2006, the first action with clear feminist goals, was not a social movement in the strict sense of the word, but a cultural movement. Referring to the women who were pioneers in the historical dimension and the background of women’s movements, the author calls the Mahsa movement the first inclusive women’s movement because women’s demands were at the center of it and men played an undeniable role in it.

Structural Contexts of the Mahsa Movement

To explain the structural contexts of the spread of public discontent or protest movements and actions, the book refers to the macro-political transformations within Iranian society, including the relationship between the government and society. Two fundamental shifts in Iranian society after the Green Movement in 1388 (2009) are discussed. The first shift is related to the gradual transformation of the theocratic state into a totalitarian state (Section 5, pp. 172-202). In the author’s view, this transformation is related both to the increasing role of the leadership in the authoritarian administration of the main institutions of power within the state apparatus and to the set of policies that have been implemented since 1388 (the suppression of the Green Movement) in relation to the repression of various protest movements and human rights activists, environmentalists, feminists and other civil society forces or artistic, cultural and sports figures. The use of security forces, the Revolutionary Guards, and the Basij as arms of repression in society intended to create collective fear through direct violent confrontation with those who protested for various reasons, particularly the nationwide collective actions such as those we witnessed in 2017, 2019, or 2022. The book mentions a « thanatocratic government », or a political system that continues its rule by killing people and inspiring fear through it. The official government discourse seeks the main roots of protest movements not in the inefficiency and pathological functioning of official institutions and ignoring the demands of the people for the democratic rights and human dignity of citizens, it pretends that they were conspiracies of the enemies, namely the West, and especially the United States, while a number of officials implicitly or explicitly recognized the existence of widespread dissatisfaction in society.

The second turn refers to the growing gap between society and the government (Part 6, pp. 203-220). The author points to the confrontation between a secular society and the theocratic government as one of the main aspects of the current political crisis in Iran. The government’s efforts to change society and to compel citizens to conform to restrictive religious norms, the government’s values, and to legitimize the principle of Velayat al-Faqih have not yielded much results, and important parts of Iranian society have turned away from the theocratic government’s culture and discourse. In other words, new and expanding values and behaviors in society, which are considered signs of individuality and constitute the new citizen’s subjectivity are more than ever replacing revolutionary utopia, the culture of sadness, and government’s ideology of death worship and self-sacrifice. The spread of the Internet has caused the new generation of Iranians to be connected to today’s world in a networked manner.

The author discusses the gradual delegitimization of the government and its culture, and the widespread protest movements, including the Mahsa movement in 1401, which can be considered a visible manifestation of this growing gap between a secular society and the theocratic government. The author discusses the main factors behind the cultural, and mental changes in Iranian society as well as objective factors, such as the presence of a middle class and urban lifestyle, the use of the Web, the existence of an Iranian diaspora that is connected to its country, the massification of higher education and the widespread presence of women in universities, as well as the development of entertainment and a secular culture of happiness, which has in practice led to the fading of the state’s dead-centered religious culture.

A notable point in F. Khosrokhaver’s analysis of the objective conditions of Iranian society is the combination of a class approach with the subjective, cultural and political aspects of citizens. He uses the concept of the « would-be middle class”, which the author had previously discussed in his writings, including in relation to the Arab Spring, to describe the subjective mindset of the poor groups of Iranian society who are educated and belong culturally to the middle classes whereas economically, they belong to the lower classes, and the universalization of some human, political and cultural demands[2]. The book believes that the class analysis of the movement should not be reduced to the economic and standard of living aspects, and that the mental and cultural aspects of social groups are intertwined with them and should also be considered. The issue is about the relationship between the subjectivity of individuals and the sense of cultural belonging in relation to the economic situation, class position and the meaning that each group gives to its living conditions and demands.

The deep generational gap and differences and the alienation of the new generations from the official culture are spreading in a situation where the government has placed all cultural institutions and institutions that play an effective role in the socialization of young people exclusively at the service of its religious culture, turned into a totalitarian death-centered theocracy. Demographic behaviors and the changes that have occurred in the status of the family or the relationship with the institution of marriage and sexual behavior can be considered signs of cultural and identity transformation in the family and its traditional roles and lifestyle. Khosrokhavar considers the spread of cohabitation (white marriage) and extramarital sexual relations, which are considered by the government to be a clear violation of religious principles, as important cases of the endogenous secularization of society.

In conclusion, the author returns to the characteristics and fate of the Mahsa movement. In Farhad Khosrokhavar’s view, this movement failed politically in changing the system, but it was culturally successful in delegitimizing the government and expanding civil disobedience against the government by promoting a new culture of thisworldly joy and happiness. The Mahsa movement was able to challenge the government’s culture and its main symbols, such as body covering or a devout and sorrowful lifestyle, with its main message, which was the joy of life within a free body.

In his book, Farhad Khosrokhavar takes a comprehensive and meticulous look at the Mahsa movement in a country that has been called a “movement society” (Saeed Madani) due to the number of protest actions. The description and analysis of the forms of protest actions and events, the anonymous and well-known actors from the teenagers who lost their lives in this movement to the famous or young figures in the world of art, culture and sports or well-known feminists, along with theoretical discussions, make the book a readable and attractive work. What perhaps distinguishes Farhad Khosrokhavar’s book from a number of other writings is the attempt to highlight the newly emerging phenomena and meanings, as well as the remarkable innovations and creativity of this movement and the ontological (existential) aspect of protest behaviors and actions since 1401 (2022). As in his previous works, including those on the 1979 Revolution or the Arab Spring, Farhad Khosrokhavar pays special attention to the subjective and imaginative aspects of actors or existential aspects in social actions, in addition to macro-objective structures and tendencies. By comparing the dominant subjectivity on the eve of 1979 with the one of the 2010s, the author attempts to point out the profound cultural changes that social movements were both a result of and contributed to. Addressing the issue of the subjective nature of social movement activists or the role of collective imagination in the processes of formation and evolution of social movements opens up a new theoretical perspective for understanding and analyzing social movements[3]. The discussion is not about denying the importance of macro-structures and objective aspects of social and protest movements. The issue is about addressing invisible aspects within social phenomena that are sometimes less considered. The book Revolt Against Theocracy is an important contribution to theoretical discussions about the endogenous dynamics of social movements as living collective phenomena and the role of the subjectivity and intersubjective interaction of activists in giving meaning to and influencing their processes.

Endnotes

- Khosrokhavar, Farhad (1997). Antropologie de la Révolution Iranienne. Paris : L’Harmattan ; Khosrokhavar, Farhad (1995). L’islamisme et la mort. Paris : L’Harmattan ↑

- Khosrokhavar, Farhad (1993). Utopie sacrifiée. Sociologie de la Révolution iranienne. Paris : L’Harmattan ; Khosrokhavar, Farhad (2012). The New Arab Revolutions that Shook the World. London: Paradigm Publishers ↑

- See Khosrokhavar, F., Paivandi, S., Motaghi, M. (2021). Sociology and Subjective features of Social movements. Sepehr Andisheh, 1, 19-49 (In Persian) ↑

Comments are closed.