/Book Review | Reading Time: 12 minutes

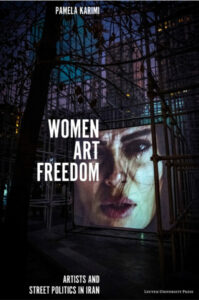

Woman, Art, Freedom

Artists and Street Politics in Iran

Nastaran Saremy | December 15, 2024

Woman, Art, Freedom: Artists and Street Politics in Iran, by Pamela Karimi is a significant contribution to the study of contemporary art in Iran, especially in relation to social transformation and contemporary political upheavals.

As the title suggests, the book is structured around key themes that, in Karimi’s view, define the art of woman, life, freedom movement, with this strong believe that the universal language of art would convey the essence of the uprising, better than any other way.

Some of these themes emerged during the peak of the protests; others, she argues, have been long-standing elements of Iranian contemporary art, pre-dating the 2022 uprising, but gaining clearer clarity and significance as the events unfolded.

The book is organized in ten chapters with an introduction, addressing ten key thematic elements that are called “acts”, each representing a distinct performative quality. These acts are pulled out of the untold narratives of the artists who actively contributed to the uprising’s performative and visual lexicon. Through interviews with artists, curators, art students and university professors, Karimi examines the transformative role of art in Iran. Combining massive fieldworks with meticulous analytical examination of these often-ephemeral artistic interventions, Karimi’s book offers a thorough and well-researched contribution to the field, making it a reliable source for scholars and researchers in the field of art, aesthetics, (political) culture studies. Furthermore, this volume serves as a significant extension of the author’s ongoing exploration of the role of art in unsettling and highly regulated socio-political spheres in Iran. Karimi’s new work shares many characteristics with her previous work, Alternative Iran, particularly in methodology and approach towards understanding alternative art forms and socio-political engagements in the Iranian context. However, there are notable differences in this work, especially in terms of exploration into the relationship between art and street politics, artivism and protest art, in the historical sense, in Iran.

Although the public and scholarly attention has been mainly engaged with the unprecedented amount of visual imagery that has been created during the uprising, this book, Karimi says, focuses on a distinct perspective on the artistic response to the events before, during, and after it. Its primary aim is to highlight the deep-rooted, often unseen artistic programming and practices that were inspired by, or significantly influenced, the movement on the ground in Iran. Karimi’s book, examines the transformative power of artistic vision in shaping the protests that surged through the streets of Iranian cities, mainly since 2009 green movement to the present moment.

In the introduction, Karimi explains why WLF’s art also matters to non-Iranian scholars. She hopes to grapple with- and redress- oversimplified prevalent interpretations in art historical literature mainly in postcolonial narratives that advocate for the preservation and autonomy of Muslim practices and beliefs but remains silence on the issues raised by the (WLF) movement in Iran. In doing so, this book not only offers insights into Iran’s context but also brings to light critical perspectives that are frequently missing from Western scholarship on MENA and Muslim societies at large. Doing so, the book adopts a feminist lens in its analysis of Iranian art; Karimi argues that the inherently “parafeminist” nature of the movement provides a more nuanced understanding of feminism and feminist art.

In the first chapter, “Parading the body on the sidewalk”. Karimi highlights the work of female artists who are primarily engaged with street and public space. This act explores a range of artworks, including the first generation of post-revolution interdisciplinary women artists- along with men, began to turn urban leftover spaces into sites of art production, those who worked with forbidden spaces such as certain cemeteries, or tried to navigate and challenge the (traditional) gendered spaces. Doing so, many choose to be subtle and discreet in their artistic expressions, finding creative avenues to be both seen and unseen, present and absent, as they have to constantly negotiate a landscape of scrutiny and control- of societal and moral judgment. The chapter then delves into a detailed examination of those who engaged with the public spaces during the movement. There was a marked increase in the number of women who ventured into Iranian cities; in the face of heightened surveillance, artists use their bodies as medium in the public, channelling their grief into art, through parading, standing, walking, rolling or other sorts of bodily intervention in various spaces.

In act two, “Hiding in plain sight”, Karimi discusses the strategies of anonymity, inconspicuousness, and obscurity which aligns with collective spirit of the uprising. Interestingly, working collectively or in anonymity is not confined to art within Iran’s borders, but is also embraced, Karimi argues, by artists elsewhere within certain diasporic communities and groups. This act also reflects on art works created behind the bar. By reviewing some of the artworks created in prison in 1980s, including painting, embroidery and then expands to a detailed review of a theatrical piece during Green Movement. Karimi describes these works as both political act and as a form of collective care. This act concludes with reflecting on works that engage with opaque bodies, mainly through bolding the invisibility of women’s contribution to the production and reproduction of social and cultural life in Iran, which is largely uncelebrated and unreported by media.

In act three, “Staging citywide protest props”, Karimi explores different types of artivism, a term underscores the dual roles that artists and activists have assumed since the series of intense antigovernment protests in recent years. This act engages with art objects as well as tools of street protest. For instance, the way hair, and bodily features once mandated to be concealed in public spaces, has transformed into symbol of liberation and empowerment. Participatory artivist works also using protest props or daily objects to engage with passerby; for instance, by using chess as protest prop, or distributing candy resembling paintballs, which caused five hundred eye injuries to protesters during fall 2022.

Act four, “reclaiming old themes for new protest arts”, discusses the subversive appropriation of old revolutionary themes and form in recent protest art. Many artists and collectives, Karimi points, are recomposing revolutionary songs, imagery, and posters from feminist themes, have also referenced leftist and communist motifs from Iran’s revolutionary past, or in sync with the prevailing visual culture of global revolutionary movements of the twentieth century, including 1968 uprising in France, decolonial movements globally. These subversive appropriations are drawn from multiple ideological histories without bowing to any, goes beyond mere influences, highlighting their universal demands for freedom from their position as dissidents.

In act five, “Reenacting Street battles”, discusses the various application of the reenactment in protest as well as artistic interventions. A significant example is the way the posture of the detained and chained Baluchi protester was replicated and then spread to other locations- not just in Iran, but around the world. Reenactment as a technique, however, has not been limited to protest; artists re-enacting nonnormative behavior in the public, protest itself, or even punishment, lashing for instance, across various spaces, captures the dynamic between the body and its surroundings, giving it nuanced meanings that showcase what Karimi calls “edgy power dynamics”. Unlike simple acts of replication, Karimi argues, “reenactments demand action through a living and breathing body that puts itself in a place where an important event has unfolded; they necessitate practice and rehearsal to effectively mimic and exaggerate the actions on which they are based”.

Act six, “documenting urban unrest”, examines the ways in which documenting of life’s struggles and conflicts as well as artistic interventions on the ground contribute to the historiography and political imagination of Iranian society. In addition, Karimi explores how these documentations carried out by artists play a role in artistic activism in Iran. This topic has already been addressed in the introduction, where she introduces “the many ways of documenting an uprising”, through listing an array of art collectives, grassroot media venues, online archives and other publications- of which some are reviewed- documenting the uprising. This act builds on these trajectories by reading innovative modes of documentations carried out by individual artists that, in Karimi’s view, also play a role in artistic activism in Iran.

Act seven’s focus, “camouflaging defiant words”, is the anarchic style poetry, mainly through introducing literary collective, and their opposition to any forms of aestheticization in literature and their “rejected” works as poets from the margins of not only Iranian cultural scene, but also its very class structure. This act then turns into poetry-performances, produced in response to WLF movement, uttering names that are usually not spoken out loud in public spaces; and it ends by looking into distinctive approaches developed by artists toward integrating space and poetry jamming, or combining tactile elements with poetry in producing art.

Act eight, “Clashing with Faith in Broad Daylight”, delves into the works of the artists who engage with and reinterpret historical themes and ideas, often through subversive appropriation. This chapter can be considered as a critical dialogue with progressive western and postcolonial academics outside Iran, who find it hard to grapple with the art and images emerging from WLF movement, such as setting veils on fire, turban throwing, etc.,as it presents a potential challenge to a Muslim believer’s way of life- when the principle of honoring traditions and religious beliefs is embedded in canonical frameworks such as postcolonial theory. WLF movement, in Karimi’s view, refreshes our views regarding fundamental questions such as what do values mean and to whom. In this respect, she investigates works of the artists that highlight these tensions; one controversial case is an exhibition at Macalester College’s Law Warschaw Gallery in Minnesota which includes illustrations depicting conservatively veiled women in ironically salacious posters, that infect campus conversations about what is happening in Iran. The exhibition paused due to the pressure and the gallery’s glass windows were covered with black curtains so that no one could look inside.

Unlike this rigid duality among Muslim diasporic community, as the examples in this act show, negotiations around religious matters and freedom of expression take on diverse forms in Iran. Extending its focus beyond secular-minded artists, this act includes believer artists who have been part of the movement, this chapter showcases a more fluid landscape of resistance in Iran. Some of the women who are questioning compulsory hijab are themselves devout Muslims. This attitude is also present in making art which is a vital, but less discussed, part of the narrative around WLF uprising. A female believer artist photographed unveiled, blindfolded women in locations outside Tehran, years before WLF. Another artist organized a performance in which the process of winding the fabric drew the women (veiled, unveiled) closer together, physically and metaphorically, weaving a visual narrative of convergence and solidarity.

In act nine, “opposing art with art in city spaces”, Karimi discusses the way artists use art as a form of resistance against official art or prescribed artistic visions, creating works that not only speak back but actively contest and challenge. The chapter goes over a range of artistic practices, including those actively oppose the repressive policies imposed by cultural institutions during the uprising, those who refused to participate in festivals, events, cancelled shows, postponed biennales, art professors suspended for supporting student protests. It then turns to review the works that sparked dispute between students and administrators, paving the way for future endeavors, in the months and weeks leading up to the movement. For instance, public artworks in Art University of Tehran campus that encourages the audience to reconsider their corporeal movements and behavior.

Act ten, “Forecasting the future”, presents, Karimi says, a series of case studies that offer an outlook on the imagined future, show different possibilities of envisioning alternative ways of living and thinking. The last act begins with the works that produced before the uprising in which images from the past appear to have found relevance in a delayed manner, which gives them a futurist character. The most prominent work that the chapter presents is an installation in an upscale gallery in Tehran, consisted of a series of large moving screens supported on a grid-like structure of scaffolding, a miniature representation of Tehran and a pointed critique of the city’s misguided urban policies, also a monument to WLF. The moving screens display silent expressions of woman as if she reflects her dreams for the future. The future is hinting at a cityscape where women, depicted larger than life, will play a central role. Other works discussed in this chapter are also envisioning the future of the Evin prison, dreaming about dismantling the notorious Evin prison, or a more playful futuristic imagination through sci-fi like narrative.

The book explores the transformative power of artistic vision in shaping the protests that erupted across Iranian cities. However, to fully understand this influence, it is crucial to investigate how these collective, and often connective, actions are aesthetically constructed. Given the aesthetic and performative dimensions of contemporary activism, there is a blur line, if any, between artistic intervention and acts of defiance. While the book attempts to contextualize art practices for greater clarity by drawing parallels between activism and art, it could have further developed this discussion by exploring the growing intertwining of aesthetics and politics in the contemporary world.

Karimi’s commitment to the ‘politics of positionality’ is evident in her presentation of the diverse experiences and vantage points of artists, shaped by factors such as class, gender, and other social identities. For instance, what act seven represents is a significant contribution to the historiography of contemporary art and its dissident interventions in the public sphere. While the role of poets and poetry in the Iranian revolution has always been celebrated and considered significant, what is striking is how the literary works examined in this act, their social associations, language, and style all fall outside the traditional canon. In fact, documenting this rejected art forms/groups, help going beyond the sublime framework that usually define politically oriented art and literature in Iran. While the book offers an extensive review of this diversity, it falls short of providing the reader with a critical or politically nuanced mapping of the heterogeneous and conflicting nature of these perspectives- which are the aesthetic configurations of collective action in contemporary Iran. These conflicts, however, are not only present within the intellectual debates in the public sphere and the art works, of which some are presented in the book, but also in the practical logic of antagonism that illuminates through WLF uprising itself. This tendency could ultimately “depoliticize political art” by reducing material conflicts- that are reflected in the works of artists and activists- to cultural issues. This neglect stems directly from the theoretical foundations of the work, particularly the ambiguity surrounding the conceptual categories provided in the introduction, where she distinguishes between political, activist, and revolutionary art. Karimi’s definition of revolutionary art fails to move beyond a focus on the sacrifices made by artists and activists, which appears to be hastily defined, and lack thorough theoretical exploration. The same issue arises when she attempts to define the relationship between art and life. Despite the prominence of ‘life’ as a central theme in both the uprising and the broader Iranian political climate, as well as its key role in defining socially engaged and community-driven art, Karimi’s exploration of the relationship between the two terms remains limited. She confines her analysis to a shift from abstraction to the body and the general presence of socio-political issues within the realm of art, which ultimately lacks a compelling theoretical depth. Finally, while Karimi introduces her concept of feminism and gender in the book’s introduction and references feminist scholars throughout, she overlooks the recent writings produced by the latest generation of Iranian feminists, for instance debates around #MeToo movement, that are shaking the long-standing power dynamics within the art scene. These efforts are also reflected in the lexicon and symbols of the uprising itself.

Karimi argues in the introduction that, like the artists themselves, who come from a variety of backgrounds, the art produced during the uprising span a wide spectrum, “intricate inquiries into culture, religion, power structures, ethics, history, memory, the rights of ethnic and minority groups, and resistance”. However, the book barely touches art, activism and artivism produced outside Tehran; had this occurred, it might have made the tensions and contradictions I mentioned earlier more apparent. The reason this tension remains overlooked is not because ‘artivism’ outside the canon doesn’t exist, but because it is rendered invisible by the author’s methodology. In the age of ICTs, which is often associated with the myth of accessibility, the author ironically points out that the book’s content primarily focuses on Tehran, because she had limited access to productions outside the capital, even while acknowledging that her primary source of contact with the scene has been through Instagram. Furthermore, given the centrality of archiving practices in this book, it is worth asking how the notion of accessibility is defined and shaped, and how this influences our reconsideration of the archive and the architecture of information and knowledge. While the act of archiving is extensively discussed in this book, what is overlooked is the politics of archive and the fact that archives—or any form of documentation—construct semantic systems, not only through the act of selection (inclusion/exclusion), but also through processes of encoding, naming, categorization, and juxtaposition.

To elucidate the point I am making, perhaps this well-known example will help. Baraye (means “For”), is a power-ballad by Iranian singer-songwriter, Shervin Hajipour, inspired by the death of Jina Amini and its aftermath, widely called the anthem of the protests. However, it is noteworthy that in response to Baraye, several ‘diss tracks’ were produced, offering critiques from the perspectives of feminist and other marginalized groups, challenging how key issues—such as gender inequality and the struggles of underrepresented communities—were not represented in the original track. This is just one example among many, and it is not limited to popular songs or imagery of the movement. It can also be traced in the artworks and interventions created both before and after the uprising. However, the invisibility of these productions and acts to many observers and scholars stems not only from their oversight or exclusion, but also from deeper epistemic barriers—rooted in the politics of seeing, naming, archiving, and the social imaginaries that shape how we understand them.

Staying true to the complexity and contradictions of this conjuncture would reveal that these conflicts are not only evident in the ways dissidence and grievances are staged or expressed, but also in the competing visions of futurity imagined by the diverse subject-positions within the uprising. In a similar vein, the final act, ‘Forecasting the Future,’ can be understood. Although the book acknowledges works and artists from diverse backgrounds, it fails to capture the essence of the conflicts central to the struggles over the future. When it comes to envisioning what lies ahead, there is little distinction made between, for instance, subaltern futurities and the polished, high-budget works produced in prestigious institutions. The future is deferred, yet not in the same way for everyone, just as our yearnings for the past are far from uniform.

* © Background Photo by Ashkan Forouzani on Unsplash

Comments are closed.