/Review Article | Reading Time: 9 minutes

Write, but Don’t Forget the Whip!

Fereshte Habibi | December 15, 2024

ISSN 2818-9434

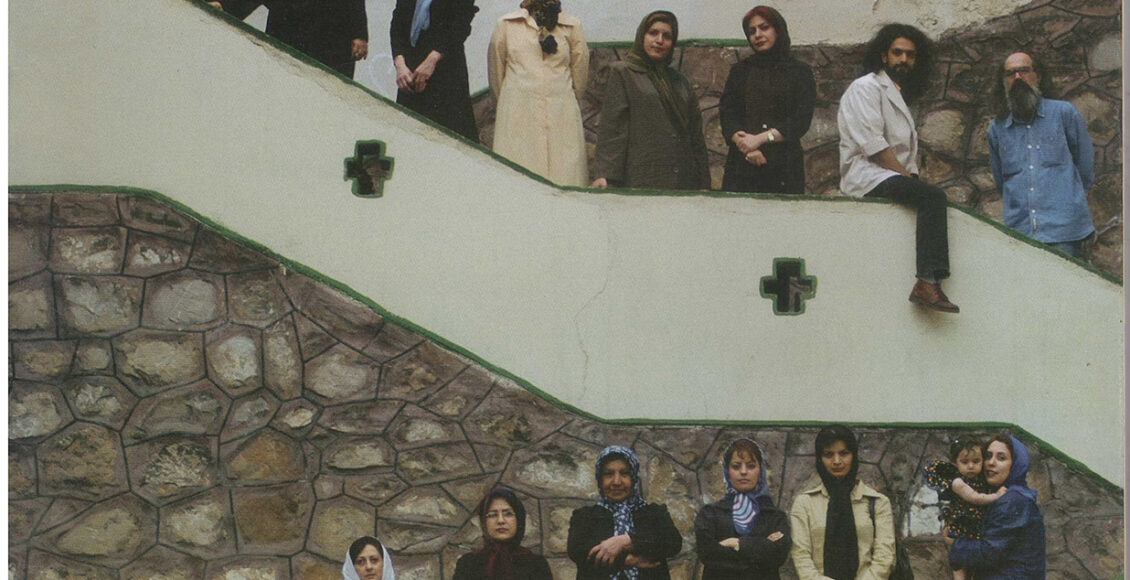

This is the 50th issue of Zanan-e Emrooz—a significant milestone for a journal we have dedicated ourselves to for years, pouring our hearts and pens into its publication. It has taken over a decade to reach this point, with each issue representing a unique journey, a new spirit, and an entirely distinct world for me.

This is the 50th issue of Zanan-e Emrooz—a significant milestone for a journal we have dedicated ourselves to for years, pouring our hearts and pens into its publication. It has taken over a decade to reach this point, with each issue representing a unique journey, a new spirit, and an entirely distinct world for me.

Writing about women during these years has often felt like “speaking on a subject while saying nothing [significant] about it.” You pick up your pen and begin, navigating a landscape overshadowed by state-imposed restrictions and the constant risk of crossing them. Writing in such conditions is both liberating and unsettling, offering freedom yet breeding insecurity. How have we managed to walk this tightrope without falling? Here, I attempt to answer this question by reflecting on our decades-long efforts to consider these imposed limits in our work while simultaneously pushing back against the invisible state-mandated boundaries.

Censorship in Iran is a multifaceted and complex issue, deeply embedded in the political, social, cultural, and legal fabric of the country. Some argue that the very existence of a magazine like this within the formal journalistic space signifies compliance with imposed limits. However, I disagree, as this perspective overlooks the fact that writing itself can be a space for negotiating the regulations designed to constrain it—especially when those regulations are subject to personal interpretations and (mis)understandings within the apparatus enforcing them. Whether we write to nudge the system or to spark small [cultural] changes, these efforts contribute to the larger current of ideas that ultimately make transformation possible.

1-The Obsession with Remaining Neutral

Anything written about women’s issues—gender and sexual relations, reproductive rights, or topics related to the female body and demands now considered basic rights—is scrutinized and judged within predetermined frameworks. Navigating the Press Law—an ordeal akin to overcoming seven trials in itself—while adhering to the Islamic Penal Code, the regulations of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, and the unwritten rules imposed by various security institutions has created a literary environment steeped in fear and intimidation. This atmosphere stifles an author’s natural passion for enlightenment and drives them toward self-censorship. Self-censorship emerges as a central challenge from the moment we begin to write. It often takes the form of retreating into the cold, detached guise of neutral and impartial language—a state I call “the obsession with a neutral pose.”

2-Should Be Defensible

The editor-in-chief’s famous saying has always been: “Write in a way that it’s defensible when they [Iranian authorities] question me about it.” A phrase that has grown somewhat overused but still serves as a familiar reference. It means that every sentence must be justifiable within the framework of the strict laws and regulations. Ensuring that the journal’s articles are justifiable—in that they address an issue but within the confines of Iran’s regulations—requires different efforts. Usually, certain words need to be phrased differently, but some of the words escape such rephrasing and remain naked and uncovered as they were. If they escape from my eyes as the editor of a department, then the editor-in-chief hunts them down. However, they may also escape from her eyes, and we hunt them only after appearing in the printed journal!

3- “We Don’t Hear Your Voice”

I never say it out loud, but I often think to myself, “The law is not divine revelation.” The individuals who create the law have taken social and cultural considerations into account, sometimes overlooking certain flaws for the sake of public interest according to a particular interpretation. These social issues, therefore, are exactly the ones we need to address. If changing social conditions require new laws, our persistent complaints must eventually reach the ears of legislators. The issue of domestic violence is escalating, yet it is frequently ignored. Women’s demands for their rights to education, employment, and child custody can lead to fatal consequences for those trapped in legal and cultural dead ends. But law enforcers avoid enforcing the law or punishing perpetuators of violence against women, yielding to the pressures of social norms or ethnic customs. In doing so, they send a clear, unspoken message: “We don’t hear your voice.”

4- The Invention of Red Squares

Zanan-e Emrooz has faced numerous reprimands for publishing images of women. Interestingly, some of these same images had been published in other journals without issue, yet we were questioned for publishing them. During our time publishing Zanan (Women) Magazine (1991- 2007), when visual censorship was even more stringent, our graphic designer often had to modify images—lengthening skirts and sleeves, blurring exposed areas of women’s bodies, and adjusting headscarves to cover more. These alterations frequently compromised the aesthetic or content value of the photographs. However, since the launch of Zanan-e Emrooz, the magazine’s graphic team devised a new and ingenious solution: the use of red squares in our two-color printing. These squares were resized to match the dimensions of the subject, strategically covering Ms. A’s legs, Ms. B’s bare arms, and Ms. C’s open neckline. This approach served as both an implicit critique and a practical solution, transforming censorship into an artistic element of the layout design.

5- The Cycle of Impossibles

Sometimes, even with the cautionary red squares, the authorities still deem the photos unpublishable. The wandering squares cannot make scenes of embracing, kissing, revelry, joy, dancing, and so on, acceptable for publication. Thus, the cycle of impossibilities is vast.

Of course, the magazine’s photographer knows how to capture photos—understanding precisely how much of the hair, face, hands, and neck can be shown to abide by Iran’s conservative laws. “Official hijab” refers to what is seen on television, not what appears on the theater stage, cinema screen, or on digital platforms. The portrayal of women differs across various outlets, as it is also influenced by the tastes of the managers or the financial resources of the media outlet. There is more freedom of expression in cinema and on platforms, where showing women’s hair styled as bangs with heavy makeup is acceptable. The image of women with shaved heads or wigs, and even unveiled women over 60, was sometimes tolerated on the cinema screen. However, these standards vary significantly when it comes to print media.

Following the demands made during the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, some individuals refuse to cover their hair in public as a protest move to mandatory veiling. The responsibly of showcasing these individuals therefore in a way to abide by Iran’s laws as well as their individual stands falls entirely on the photographer, who must take pictures in such a way that the subject’s hair is hidden under the branches of a tree, or the photo is cropped in a way that conceals any trace of hair or impermissible beauty.

6- Erasure: A Historical Experience

Censorship, in our context, often extends to all forms of cultural content. However, when it comes to media focusing on women’s issues, it seems the patterns of erasure are deeply connected to the omission of women from the history of written narratives. Feminist historiography has demonstrated that history has been constructed to highlight masculine perspectives, voices, desires, and agencies, while women have been largely overlooked, reduced to a shapeless and nameless body. The slightest trace of women in written literature is often mediated through roles and images imposed upon them by others. Women’s lives and identities have been either distorted or even fully erased through these constructed narratives.

Over the years, my ambition has been to rediscover and highlight the forgotten and erased faces and figures of women for each issue we address. I have aimed to contribute to the re-examination of women’s history by dedicating this modest platform by amplifying their unheard voices. Yet, I must acknowledge that there have been times when I, too, have overlooked certain people, subjects, and ideologies. Now, more than ever, I understand the importance of ensuring that every voice is heard, resisting the temptation to become an agent of erasure or allow the silencing hand of history to act through my actions or our collective efforts.

7- Zan, Zanbour, and Zanjan

A friend once joked that during a time [under the Islamic Republic] all words starting with “zan” (woman) were filtered—even words like zanbur (bee) and Zanjan (the city). This humorous remark captures a significant part of our history, reflecting the restrictive climate of that era and serving as a testament to how far we’ve come. “Zan, Zanbur, and Zanjan” became symbols of the filtering restrictions of the 1990s, coinciding with the days of Zanan magazine.

There was a time when the word woman was filtered as much as possible to avoid provoking trouble. In that stifling atmosphere, no one dared to write about mere movement of the female body, let alone dance. Even the word dance was forbidden, and body itself could be interpreted as an erotic term. What, then, has changed between those dark days and today? The laws remain in place, and enforcement has only grown stricter. Yet, here I am, having included an article on modern dance, accompanied by stunning photos of captivating and expressive forms, in the art section of one of our issues. How is this possible? The answer lies in the undeniable truth: society has changed. It stands miles ahead of the days of censoring words like Zan, Zanbour, and Zanjan.

8- Recent Experiences

In the spring of the 2022, following the publication of the women filmmakers’ public statement protesting violence against women in the cinema industry, I interviewed their initial follow-up committee to highlight their cause and ongoing efforts of the previous years in the print media. Although the atmosphere in those days was less strict compared to the extensive surveillance and censorship we later experienced after the Women, Life Freedom protests just months later, the impact of threats and intimidation from opposing groups, particularly within the cinema community, was clearly visible. Even our interview faced difficulties. Many reputable figures of the industry, prominent women and men, even the lawyers and legal advisors were not yet on board with this demand. Some of the female figures who had initially stepped firmly into the field withdrew their public protests due to threats and intimidation. There was a lot of discussion and commentary around the issue, and we had to draft the group interview carefully, anticipating all possible reactions and backlash. We were forced to retreat as a result of such pressures, and out of an abundance of caution we sent the draft of the interview to a lawyer friend for advice. He returned it with half of the content deleted, deeming those sections unpublishable. I implemented all the suggested deletions with the editor-in-chief’s agreement. But then, we reconsidered and reinstated everything we had removed.

The editor-in-chief and I shared a mutual determination—perhaps a shared madness—to take on the unknown risks of publishing the full interview. I remain deeply grateful to her for her flexibility and courage in standing by this decision.

9- Post-Publication Censorship

The shrinking intervals between social crises in Iran, the limited capacity of the state to address escalating social issues, and the introduction of new regulations that have fueled public anger have created a challenging environment for the press in recent years, resulting in a wave of legal prosecutions and a crisis of journalists being imprisoned.

As journalists faced increasing despair and insecurity, which proceeded with more restrictions on press freedom, the scope of activity in cyberspace—from information production and analysis to distribution—expanded significantly.

Today, most people turn to cyberspace and unofficial media for their daily news, as interest in official publications, even the independent ones continue to decline. Despite this shift, supervisory institutions persist in imposing awkward restrictions, making the publishing of an authorized print journal even more challenging. The editor may be summoned after an issue is published and asked to change the cover. She may be forced to release a new edition with a redesigned cover and retrieve the previous edition!

10- Write, But Don’t Forget the Whip

In preparation for my interrogation meeting, I reminded myself to emphasize that I have been writing about women for an authorized print journal for over twenty years, making me well-acquainted with the red lines. I understand the language I need to use and the extent to which my skills and knowledge can support me in negotiating with the law. I know the limits in recording interdisciplinary concepts related to women and art and [feminist] rereading of the history.

I consulted my lawyer friend before the meeting to understand my legal rights and boundaries. I had repeatedly reviewed my articles, trying to identify which ones might have led to my summons. What had I written, and where, that crossed into the realm of the “should nots”?

In my most hopeless and lonely moments, I have chastised myself: So what? What is the point of spilling a handful of words onto a piece of paper and engaging in this futile struggle? During the difficult and anxious days leading up to the meeting, the waiting drives me to self-blame and a denial of everything I have accomplished so far.

However, the interrogation scene was nothing like I had heard or imagined in my nightmares. The interrogator didn’t ask a question I could respond to with eloquence. Instead, I found myself offering the most trivial and meaningless answers that came to mind. He gave me a warning, a reprimand, and that was all.

The days that followed were a blur of paralysis and denial: the inability to write, fear of its consequences, and a rejection of its significance. It took time for me to remember that I must keep writing, despite the looming threats. I must write because I know no other tool that pursues change and understanding so peacefully. Adorno once said that those without a home build one through writing. Writing is my home, and words are the tools of my life. If my home is destroyed, I will build another with words.

Comments are closed.