Is there such a thing as a universal policy for women’s empowerment (or disempowerment)? Can there be a fixed response among gender advocates to any specific policy? The long international history of state and society involvement in women’s dress and behavior, including both the formal segregation of some otherwise public spaces and the mandatory wearing or removing of certain garments, should remind us that these are messy issues. Arguments for placing restrictions on women’s mobility (access to public spaces) or clothing are often explicitly framed as issues of modesty and/or security, freedom and/or agency. Implicitly, they are often understood as competing claims on identity and community. “We” behave a certain way. “Our women” who behave a certain way have a claim on the protection of the state and society. This superficial signposting of identity claims and ideologies obscures the complex negotiations and outcomes of on-the-ground actions. Yet time and again, reductionist, binary arguments are made that only one way of doing things is appropriate for women’s wellbeing, however that may be defined. A policy is either good or bad, automatically confers individual freedom or automatically restricts human potential; a behavior is either moral or immoral. Yet as with most social policies, especially those dealing with gender, it’s the details that matter.

By details, I do not necessarily mean the exact formal workings of a legal framework. Rather, our attention should be focused on the specific negotiations of power and the experiences of practice. These structure the formulation, implementation, and implications of any policy, and shape its significance in daily life. They are not simply matters of ideology, but of day to day reality. And it is within that complexity that we can actually observe the realities of women’s experiences of empowerment and limitation. The challenge of evaluating any formal state policy lies in evaluating the details of state and society interaction, understanding that they are mutually, unevenly, and dynamically constructed. Who advocates for, and who benefits from a particular policy? What are its intended outcomes, and is it appropriated for alternative goals by those whom it targets? What are the various arguments endorsing or countering a policy, who do they appeal to, and how effective are they? These are the questions that need to be explored in evaluating both policies and practices of gender segregation and hejab.

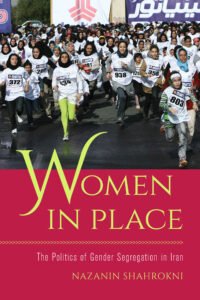

In her book Women in Place: The Politics of Gender Segregation in Iran, Nazanin Shahrokni attends to these complex relations of negotiated power and every day practice. The book is a study of three different policies of gender segregation in Tehran: on buses, in parks, and in stadiums; and how these policies have or haven’t changed. Sharhokni did extensive field work in Tehran investigating how these policies came about, examining the arguments made for them, the coalitions that worked together (often uneasily) to bring them about, and the experiences of the ordinary women subject to them. She finds that each one is different, and that the examination of each provides different lessons for achieving policies that will substantively improve women’s wellbeing. Her research engages at multiple levels of policy formation, but is not a long term exploration of experiences of or attitudes towards gender segregation or gender mixed spaces, or an exhaustive study of all Iranian gender segregation policies. Her discussion of gender segregation in public transportation focuses on buses, not its later application to metro cars. She does not address gender segregation in primary and secondary education, and its relative absence from Iranian university education. That is a policy topic that has been more extensively covered in scholarship and informal social analysis. Iranian women have maintained their right to (mostly) equal university education by broadly challenging the postrevolutionary state’s recurring efforts to limit their access. But few now consider gender segregated primary and secondary schools to be a barrier to girls and young women’s development. The enormous gains in women’s literacy, and the remarkable absence of a significant gender gap in literacy rates among recent generations, testify to the effective success of girls’ schooling. In turn, these successes have made all girls primary and secondary schools less of an ideological issue.

![]() In particular, her book provides an extraordinary study of how some gender segregation policies embody a quiet contradiction: when gender segregation plainly expands rather than limits women’s access to social resources, it can be a surprisingly effective strategy for women’s further social integration.

In particular, her book provides an extraordinary study of how some gender segregation policies embody a quiet contradiction: when gender segregation plainly expands rather than limits women’s access to social resources, it can be a surprisingly effective strategy for women’s further social integration.

![]()

By contrast, the examples Shahrokni does discuss have not been so well studied, and provide groundbreaking research that should promote further fieldwork based research on the modern experiences and implications gender segregation in public space. In particular, her book provides an extraordinary study of how some gender segregation policies embody a quiet contradiction: when gender segregation plainly expands rather than limits women’s access to social resources, it can be a surprisingly effective strategy for women’s further social integration. This has been the case with the provision of designated women only spaces on public transportation and women only public parks. These new gender segregated spaces did not formally restrict women from shared space and did not create new men only spaces. (When gender segregated buses were first introduced the policy intended separate buses for men and women; this quickly became unwieldy as families found it impossible to travel together, and the policy of exclusive provision of women and men only buses was dropped.) Instead, the women only spaces were created within and in addition to existing shared spaces that in fact were often dominated by male presence.

These new women’s gender segregated spaces were a response to the widespread lived reality that shared public spaces are often in fact experienced as primarily available to men and even hostile to women’s use. This is not only the case in Iran, or in Muslim majority countries. Women’s right to public space is regularly contested not only by formal gender segregation but primarily by informal attitudes, harassment, and aggression against women perceived as stepping beyond their appropriate space or sphere. Under these globally widespread conditions, the provision of newly gender segregated access to social resources may have encouraged some Iranian citizens to presume that women’s access should be gender segregated, even if that was not the design of the policy. Yet designated women only spaces can contribute to expansions in women’s spatial mobility, claims to public space, and their right to the city. The simultaneous continued provision of integrated spaces on public transportation and in public parks enabled many women to learn to access a social resource more easily. The experience of safe public spaces and approved access to them may have led some women to feel more comfortable claiming their share of the existing mixed gender spaces, whether on buses, in parks, or elsewhere. Whatever backlash women in mixed spaces may be perceiving, the provision of designated women’s spaces on public transportation established that women had the legitimate right to move on their own, unaccompanied by a man, through the city. Similarly, the provision of women only parks established that the state has an obligation to provide for women’s physical activity and access to public green space.

Shahrokni’s first case study is of gender segregated buses. Iran became a majority urban population in 1979. But the revolution sharply increased internal migration to major cities, especially Tehran. Overcrowding quickly became an issue. Previous models of private housing and transportation were inadequate to new conditions, and municipalities began to consider reforms to the woeful state of public transportation, while supporting apartment towers as a denser residential model. To keep cities, and especially Tehran, functioning, more people needed to be able to take the bus. In order to get more people to take the bus, women’s access had to be better enabled. Gender segregated buses were proposed in order to facilitate women’s mobility, getting them into public transportation and out of private cars. The policy also was a clear endorsement of women’s spatial mobility. Rather than attempting to move women out of the street and back into the home, Shahrokni shows that gender segregated buses were intended to move them more effectively through the streets, and to facilitate their ability to get where they wanted to go. It opened up possibilities for women to move through and into non-domestic spaces, whether economic or educational. As a policy, the provision of designated women only spaces on shared buses demonstrated that both society and the state had recognized the value integrating women into systems of education and work. As a practice, gender segregated buses (and eventually women only metro cars) facilitated enlarged social and economic mobility and integration.

![]() Rather than attempting to move women out of the street and back into the home, Shahrokni shows that gender segregated buses were intended to move them more effectively through the streets, and to facilitate their ability to get where they wanted to go. It opened up possibilities for women to move through and into non-domestic spaces, whether economic or educational.

Rather than attempting to move women out of the street and back into the home, Shahrokni shows that gender segregated buses were intended to move them more effectively through the streets, and to facilitate their ability to get where they wanted to go. It opened up possibilities for women to move through and into non-domestic spaces, whether economic or educational.

![]()

Shahrokni’s second case study is of women only parks. Gender segregated parks—the creation of parks exclusively for the use of women and children—were proposed in response to concerns about women’s physical health as well as demands for more accessible green space. Once apartment living in towers became a common and accepted form of residential housing, women no longer had access to the secured private open space of domestic courtyards. This led to concerns around lack of exercise space, and inadequate exposure to sunlight in order to supply adequate vitamin D. Proposals for alternative secured public open spaces (women’s parks) were justified in terms of medically approved leisure. Since they were established, women have made much more varied use of the parks than simply regarding them as a medical resource. But the incorporation of the apparently non-ideological arguments of modern medical science helped support the creation of new gender segregated spaces that function by excluding men from access they previously enjoyed. Parks that had been open to men and women, even if mostly men made use of them, provided expanded access to women through gender segregation that functioned by withdrawing access to men.

The initiation of gender segregated buses (and eventually the addition of women only metro cars) expanded infrastructure that could be justified by the state in terms of economic need and urban logistics. The park example reveals something else. The creation of the gender segregated parks depended on the success of the medically justified arguments that the state needs to care for the population’s health. Women’s activism was also crucial. But adequate exercise, fresh air, and sunshine are not always regarded as urgent necessities. Even if they are acknowledged as such, it is clear that many states and societies have been quite willing to allow much of their population to go without until the poor health of the workforce becomes both a chronic and a critical problem to the economy and the military. A state that concerns itself with its citizens’ adequate access to green space for exercise and leisure is a state pursuing the modern biopolitical model of governance. Rather than a sovereign who rules subjects entirely through the threat and spectacle of violence, a biopolitical model of governance depends on a more mutual social contract between the state and its citizens. In return for loyalty and acquiescence to governing authority, the state becomes more responsible for not just the existence of its population but the wellbeing of its citizens. Any state relies to some degree on its legitimate right to the use of violence. But the biopolitical model presumes violence as a last resort. Instead, state and society are fused together by a social contract that withdraws the immediate threat of force for the promises of wellbeing. The state’s responsibility it to manage the population as a whole in order to provide for the potential of the good life at the individual level. This model is not often fully achieved by any state, whether in terms of the provision of wellbeing or the withdrawal of the use of violence on the populations. But the implementation of the policy of women only parks indicates that the Iranian state is functioning at least to some extent on the model of modern biopolitical governance. The older model of the more absolute sovereign may continue. But it is now in competition with a governance model that justifies itself politically through intensive, scientifically rationalized management of the population.

That conflict between Iranian models of governance is more evident in the third example Shahrokni discusses, of gender segregation in sports stadiums. The previous two examples of gender segregation in buses and parks demonstrate the contradiction of a policy that simultaneously restricts entrance and expands women’s access to public space and public goods. In this respect the policies of gender segregated buses and women only parks are similar to the policy of gender segregation in primary and secondary schools. Whatever the specific intentions of these policies, including their partial justifications on arguments of moral security, they have clearly resulted in expanding and legitimating women’s rights to spatial and physical mobility and educational parity, and emphasized the state’s responsibility in securing those rights. But not all gender segregation policies are structured with this benign ambiguity. The gendered segregation of football stadiums has remained a stubborn model of restriction on women’s social participation. This may seem surprising given that the issue of Iran’s gender segregated football stadiums became an international controversy and received much more attention in the global popular imagination than any of the other examples. Given the significance of football as a national sport and symbol, and the national stadium as the central location and focus of popular participation through spectatorship, it is not surprising that in the global popular imagination the gender segregation of Iranian stadiums has become a defining example of the state’s stubbornly backward gender policies. Women’s exclusion from stadiums is taken to symbolize women’s exclusion from full civic participation in the national game. But Shahrokni shows that the policy notoriety may itself have made the policy more intransigent to change.

![]() The gendered segregation of football stadiums has remained a stubborn model of restriction on women’s social participation. This may seem surprising given that the issue of Iran’s gender segregated football stadiums became an international controversy and received much more attention in the global popular imagination than any of the other examples.

The gendered segregation of football stadiums has remained a stubborn model of restriction on women’s social participation. This may seem surprising given that the issue of Iran’s gender segregated football stadiums became an international controversy and received much more attention in the global popular imagination than any of the other examples.

![]()

As opposed to buses, parks, and schools, gender segregated stadiums have become a symbol of the state’s role as sovereign, rather than its responsibilities as biopolitical guarantor. The ongoing competition between these two governance models has made desegregation of the stadiums, or even the provision of separate segregated spaces for men and women, too politically significant to address as a mere problem of sports spectatorship. Efforts to formulate an effective national coalition that could effectively harness the legitimacy of biopolitical arguments have been complicated by the combination of international pressure on the stadiums issue and national ambivalence about intersections of class and gender among football fans.

Arguments against desegregating the stadiums have often been made on the basis of the stadium atmosphere: that it is too rowdy, to impolite for women to be comfortable there. Coming from conservative elements of the state, these arguments can seem specious. When they are made by apparently ordinary women football fans, they can seem prissy. Isn’t the point of in-person spectatorship to be able to join with others in screaming support for your team? But the vociferous passion of football supporters, in Iran and elsewhere, has often edged into something more extreme. Known in different places as football “hooligans” or “ultras,” loosely organized, all-male gangs of hyper-partisan team supporters have been notorious all over the world for their aggressive partisanship and propensity to violence. Concerns about the atmosphere in stadiums, and the risks of brawls and attacks outside the stadium before and after games when supporters from competing teams encounter each other, have led authorities in many countries to make efforts to redesign stadiums and more effectively control fan behavior. These reforms to spectator management have often been presented as efforts to make the games safer for in-person fans, or more family-friendly. Since stadium “hooligans” or “ultras” are usually associated with male working class identity and behaviors, these same reforms are often implicitly about making stadium attendance more attractive to the middle class.

In Iran, these reforms to the management of popular behavior are stymied precisely by the stand-off between the sovereign and biopolitical models of state power, as well as by tensions over intersections of class and gender. It is hard to mobilize effectively at the local level for a cause that inevitably can only effect a relatively privileged few, who themselves may disdain the volatile behaviors and class identity of their potential fellow stadium spectators. The state as sovereign, pushing back against external demands and internal lobbying for women’s in-person spectatorship, can claim that maintaining gender segregated stadiums preserves more vulnerable segments of the population (women and families) from risk by undesirable elements (working class men). But the biopolitical state has difficulty mounting an effective counter argument for opening the stadiums to women fans as a generalized group. Despite the associations with disruptive working class behaviors, in-person tickets to stadium games are a middle class luxury. Football games by the major teams are broadcast on state television, which is how most people, men and women, watch them. After a big win, the state tolerates both male and female fans erupting into the streets, yelling, dancing, their faces painted in team colors. Many people may believe women as well as men should in principle have the right to see the games in person. But the biopolitical state would need to argue simultaneously that opening the stadiums to women fans would fulfill a legitimate, general women’s need (across class lines) and that it could ensure the security of that fulfillment (by managing male working class behavior). Since that argument would actually set the biopolitical state as the inevitably resented arbiter of a competition between middle class women and working class men, there is little incentive for a major policy initiative in this direction.

![]() Many people may believe women as well as men should in principle have the right to see the games in person. But the biopolitical state would need to argue simultaneously that opening the stadiums to women fans would fulfill a legitimate, general women’s need… and that it could ensure the security of that fulfillment…

Many people may believe women as well as men should in principle have the right to see the games in person. But the biopolitical state would need to argue simultaneously that opening the stadiums to women fans would fulfill a legitimate, general women’s need… and that it could ensure the security of that fulfillment…

![]()

Compromises can be made. International pressure from FIFA and world opinion on the stadium issue helped open Azadi Stadium to a limited number of in-person women spectators for the 2019 World Cup qualifying game. Acquiescing to external pressure and the notoriety of the tragic death of the “Blue Girl” a month before, 4,600 tickets for women were made available for a stadium that can seat 78,000. Women fans who could get tickets were ecstatic. Shahrokni’s book was published too early to discuss this occasion. But her overall analysis makes clear why this high profile, one time policy compromise isn’t necessarily indicative of lasting policy change. Shahrokni discusses how internal policy positions had already solidified through previous factional struggles over the stadium issue. Arguments over women’s right of access were appropriated to larger struggles unrelated to gender issues. When the sovereign state did have to make a policy exception and allow women spectators for the 2019 qualifying game, it grudgingly accommodated to international pressure rather than to the logics of biopolitics or local claims for more inclusive social welfare.

Both class and gender are barriers to stadium spectatorship. Even for the 2019 World Cup qualifier, the stadium was not sold out. Millions may watch the game, but only a few thousand with luck or cash to spare can buy tickets. Women only parks are not only or even primarily for elites, who can pay for private sport club memberships and may have their own second homes and land for recreation outside of urban centers. Gender segregated buses transport ordinary students and workers to their schools and jobs, while the wealthy can rely on private cars and privately hired transportation. The argument against gender segregated stadiums cannot be made on similar bases of broad inclusivity and general population wellbeing. Unlike the proposals for new gender segregated spaces on buses and for women only parks, the arguments to lift the general ban on women stadium spectators have to argue against rather than for gender segregation. These arguments also have to advocate for an aspect of women’s social integration that cannot be made in the name of easing general hardship or providing a societally recognized necessity. Despite the passion of some Iranian supporters for women’s stadium access and the relatively high level of international scrutiny the issue received, the problem seems to be stuck.

More recent controversies over bicycle highlight how tensions between elements of the state may also be leading to changed relations between state and society. Ride-share bicycles have been available in Tehran to both men and women since 2019, and during the pandemic there was more widespread support for cycling as a means of local transportation and in order to get fresh air and exercise. These arguments were often reminiscent of the earlier interventions around public transportation and green space, making use of biopolitical logics for managing improvements to the population’s access to the city and good health. The public health crisis made medical justifications even more salient, and family and collective bicycle riding was encouraged. Pushback against women’s cycling has been framed through religious justification and a sovereign model of authority. But the shift in balance between sovereign and biopolitical models of governance has been evident in the noticeably archaic arguments against women’s bicycle riding that have been mobilized in opposition to former Tehran Mayor Pirooz Hanachi’s efforts to encourage cycling for all: that the Qur’an prohibits women’s horseback riding; that since there is nothing in the Qur’an about bicycles, it is haram. The reliance on scholasticism to support a sovereign prohibition against a relatively innocuous leisure activity has been noteworthy. So has the determination of women cyclists simply to ignore the state and openly cycle down major public streets like Enghelab in Tehran. Women cyclists know that they have some higher state support, as well as some state opposition. They also know that riding a bicycle can be a remarkable experience of physical autonomy and spatial freedom. Nineteenth century women’s movement activist and bicycle riders already realized this: Frances Willard, the nationally prominent leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, even wrote a book in favor of bicycle riding, and named her bicycle Gladys.(Willard, 2014[1895]) As Willard wrote, “reform often advances most rapidly by indirection.” Even without formal policy change, social practices around women’s public presence, spatial mobility, and general social integration continue to open up.

References

Willard, Frances Elizabeth. 2014[1895]. Wheel within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle. Evanston, Illinois: Frances Willard Historical Association.

© Background Image in the Home Page: Photo by

© Background Image in the Home Page: Photo by

Comments are closed.