Cinema Hell: Six Reports on Human Incineration at Cinema Rex

Karim Nikunazar

Nashre-Cheshmeh Publishing House, Tehran 2020

Karim Nikunazar is a journalist, film critic, writer, and founder of Tragedy Radio podcast and Tragedy Book bimonthly.

More than four decades have passed since the Cinema Rex tragedy in Abadan, on August 19, 1978, brought the Pahlavi regime closer to the brink of downfall. Yet many questions remain unanswered. Cinema Hell: Six Reports on Human Incineration at Cinema Rex by Karim Nikunazar, recently published by Nashre-Cheshmeh Publishing House, examines this incident. The book is an accurate and fairly thorough account of the fire incident in the Cinema Rex in Abadan. Four decades after the calamity, there is no sound information on the various aspects of the incident, more specifically on the actual purpose and plan of the perpetrators, who were a few young religious men from the low-income neighbourhoods of Abadan. At the time, the Pahlavi regime publicized the Rex Cinema fire to be the work of “Islamic Marxists”. As stated by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, “Instead of a great civilization, they afflicted people with great terror.” But the revolutionary forces accused SAVAK, the Shah’s notorious secret police, of perpetrating this crime to discredit the Iranian Revolution and veer it from its main course. Two years after the Revolution, even with the confession of the perpetrators in court, it was still unclear who locked the cinema’s exit doors and with what intention, leaving no chance for the petrified audience to escape. This book does not answer this question either. Nikunazar, a native of Abadan, draws our attention to other facets of this tragedy. Incidentally, his family lived in the same neighbourhood as Hossein Takabalizadeh, one of the main perpetrators. Since Nikunazar grew up in the same neighbourhood, he had heard different stories about the Cinema Rex incident. He draws on all these stories to talk about the motives and perceptions of the young people behind it, comparing and contrasting the documents and writings on the tragedy with his own hearings.

While analyzing both official and unofficial narratives of the event, Cinema Hell tries to produce an account based on more recent documents and evidence that have received less attention. He even relies on scattered rumours to embed the tragedy in the context of the cultural and social tensions of Abadan during the Revolution. By putting oral information and manuscript documents together, he takes his readers to the heart of the Rex Cinema fire. He explores the decision to burn the cinema in the context of Abadan and the lives and thoughts of the city’s religious youth in the 1970s. The book helps the readers to understand the goals and perceptions of the Revolution among different groups of revolutionaries in its historiographical context. These differences seemed insignificant at the time, as highly heterogeneous and opposing forces had come together under the banner of the Unity in Words (vahdat-e kalameh). However, their crucial significance became evident in many ways the day after the Revolution.

Nikunazar, a screenwriter, journalist, and film critic, has spent years doing fieldwork and archival studies about this abominable event in his hometown. Finally, he has written this new account, full of new information, that can undoubtedly shed new light on this event. Cinema Hell brings together the shadows, the people, and the whispers that went hand in hand to create this harrowing arson. After forty years, this human burn pit is still a recurring story that invites further reflection. It is safe to say this book provides the reader with documents, narratives, and analyses that have hitherto remained uncovered. Writing a fact-based story, Nikunazar removes the hot ashes to discover who set the Rex Cinema on fire.

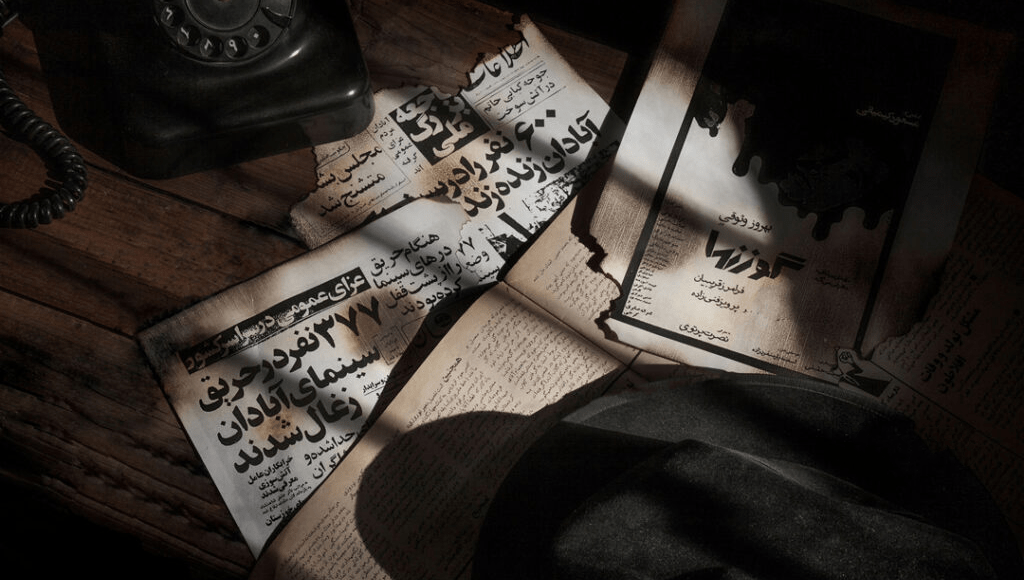

The public learned about the event by newspaper reports during the turbulent days of 1978. On Sunday, August 20, 1978, Etela’aat’s editorial wrote:

In a national tragedy that took place last night in the city of Abadan, 377 men, women, and children burned alive in the Rex Cinema. At 10 o’clock last night, while 700 men, women, and children were watching the Persian movie The Deer in the theatre, a group of saboteurs who did not believe in any basic human principles set the cinema on fire with flammable materials. The cinema custodian assisted them. The fire quickly engulfed the entire cinema hall. Men, women, and children rushed to the cinema entrance and exit doors as soon as they saw the fire but encountered locked doors. Fire engulfed the entire hall, and flames surrounded the howling and screaming viewers. All in all, 377 spectators, men, women, and children, were horrendously burned alive in the fire. Immediately after the fire started, the Fire Departments at Abadan Municipality and the National Iranian Oil Company rushed to extinguish it. Firefighters managed to contain the blaze by 2 a.m. Today, authorities are trying to remove the bodies of the 377 viewers burned alive in the fire.

Along with the news in the media, religious revolutionaries, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, denied the tragedy had anything to do with them. In his statement on the Rex Cinema incident, Khomeini stated that:

Receiving the very tragic news of the burning of several hundred of our compatriots in such a calculated manner caused me great shock and sadness. I do not believe that any Muslim or human being would commit such a brutal atrocity, except those accustomed to such actions and those whose bestiality has deprived them of any sense of humanity. What is certain is that this inhuman and anti-Islamic act could not be attributed to the Shah’s opponents. From whatever persuasion, they have risked their lives to protect the interests of Islam and Iran and the lives and property of the people. They sacrifice their lives to defend their compatriots. The evidence proves the criminal hand of the oppressive system is at work to deliberately distort the image of the humane Islamic movement of our nation in the world. Starting a ring of fire on the entire premise of the cinema and then sending your stooges to lock the doors can only be done by people in charge of the whole situation.

So entrenched were these ideas that when in 1980, two years into the Revolution, the trial of the perpetrators of the fire began, the new government leaders hoped that the main defendant, Hossein Takabalizadeh, would identify himself as a SAVAK operative taking orders from the then government. But he refused to go along with this story. When the judge asked him if he had committed the crime on the orders of SAVAK, Takabalizadeh was infuriated and rejected such an accusation.

Cinema Hell explores the narrative of tragedy from four different perspectives: The first is Hossein Takbabalizadeh’s rendering, the  primary defendant in the trial and the only survivor of the four-member group responsible for setting the cinema on fire. Takabalizadeh’s accounts, the only document about the incident in his own words, explain that he, along with three others from his neighbourhood, planned to set a cinema on fire in support of the Revolution on the night of August 19, 1978. They chose Cinema Rex by mere accident. “I went home. The kids came and said we wanted to set a cinema on fire. We then prepared four small glasses filled with thinner and went to Soheila Cinema. We threw the glasses on the floor from the waiting room inside the cinema. Then I lit a match, but it did not catch fire.” He explained that the thinner must have dried quickly and did not work. They return to Soheila Cinema, this time with a new incendiary glass made by Faraj, another group member. Others in the group did not know how Faraj got hold of the incendiary glass. But Soheila Cinema was closed. In search of another cinema, they arrived at the Rex Cinema. Takabalizadeh confessed that after his friends sprayed the contents of the thinner and oil containers on the waiting room walls, he lit a match and, frightened by the fire, returned to the movie theatre. He said he never thought so many people would burn alive in the cinema, believing they could escape the horror.

primary defendant in the trial and the only survivor of the four-member group responsible for setting the cinema on fire. Takabalizadeh’s accounts, the only document about the incident in his own words, explain that he, along with three others from his neighbourhood, planned to set a cinema on fire in support of the Revolution on the night of August 19, 1978. They chose Cinema Rex by mere accident. “I went home. The kids came and said we wanted to set a cinema on fire. We then prepared four small glasses filled with thinner and went to Soheila Cinema. We threw the glasses on the floor from the waiting room inside the cinema. Then I lit a match, but it did not catch fire.” He explained that the thinner must have dried quickly and did not work. They return to Soheila Cinema, this time with a new incendiary glass made by Faraj, another group member. Others in the group did not know how Faraj got hold of the incendiary glass. But Soheila Cinema was closed. In search of another cinema, they arrived at the Rex Cinema. Takabalizadeh confessed that after his friends sprayed the contents of the thinner and oil containers on the waiting room walls, he lit a match and, frightened by the fire, returned to the movie theatre. He said he never thought so many people would burn alive in the cinema, believing they could escape the horror.

Takabalizadeh’s account of the tragedy focuses on his assertion of his innocence based on his “ignorance” of the consequences of his action: this includes his unfamiliarity with the interior of the cinema, his ignorance that the cinema lacked fire extinguishing equipment and walls lacked proper acoustics, and his ignorance of the power of flammable material. So, he never realized the high risk involved in endangering the audience’s lives. Nikunazar strives to problematize this narrative by revealing what motivated these poor religious youth was their mental violence against the “other” culture. In their eyes, the Revolution was to eliminate this culture from society. He examines Takabalizadeh’s life in poverty and how he joined religious groups opposed to the regime. Hossein spent six months in prison for stealing the bicycle of an Oil Company worker when he was 12 years old. But this was not his last imprisonment; he was 17 years old when he started to sell cannabis in the city park, Bagh-e Meli, and gradually became a famous drug dealer in Ahmedabad. He also consumed every kind of drug he sold. However, he did not want to remain addicted to drugs, knowing other youths from Cuba to Algeria and Palestine, were engaged in armed struggle. The idea of travelling to Palestine flashed through the minds of Hossein and his friend, Zaghi. They were seeking redemption by going to Palestine. Takabalizadeh wanted to be a hero, not a heroin addict. They looked for a smuggler to take them to Palestine through Syria. But they did not have the money. Then they realized Abadan was calling on them, too, so they saw no need to go to Palestine to fight. January 17, 1978, when news of the demonstrations and the massacre of the people of Qom reached Abadan, many people took to the streets, propelling the beginning of protests in Abadan. Hossein and Zaghi both joined the protests, marking a new chapter in their lives.

Nikunazar goes beyond the perpetrators’ motivation for the crime and describes how authorities were unable to handle the crisis by recounting their reaction to the calamity. The officials and managers are described as having no other goal but to erase all traces of the crime, treating the people burned in the cinema the same as the victims of the army shootings in the streets. We read that Gholamreza Zarabi, the prosecutor of Abadan, was informed of the incident at one o’clock in the morning on August 20 and immediately went to the cinema. What he saw was a complete catastrophe. The floor of the cinema was full of burnt and half-burnt bodies. Remains of the dead and fragments of unidentified bodies were on the ground. Not much time had passed, but some of the bodies had started to smell due to the heat. The smell of burnt bodies and decaying corpses was a grim scent that was forever etched in the minds of everyone who entered the Rex Cinema that night after the tragedy. Before the sun rose on August 20, 1957, all the burned corpses of Cinema Rex had been transferred to the city cemetery. City workers and police were ready to quickly load bags of charred bodies and body parts into two trucks to send to the cemetery. By orders from Colonel Razmi, City Police Commander, the cemetery guard and municipal workers were ready to bury all the bodies in a large pit at 4 a.m.; however, Zarabie, the prosecutor, put a stop to this till all the bodies were counted and identified. A hundred and six victims were identified, but a hundred and twenty were burned beyond recognition. The death counts were also different: the governor of Abadan announced that 337 people burned in Rex, the prime minister said 306, and the registered number in the Ministry of Justice court file was 403.

The third lens opens to the ruling revolutionaries’ view of the incident through the trial proceedings for Takabalizadeh, held on September 24, 1980, one week after the tragedy’s second anniversary. The trial was presided over by Seyyed Hossein Mousavi Tabrizi at the Abadan’s Cinema Taj. Running for 20 sessions in 10 days, Takabalizadeh confessed in the court that he and his two friends, Yadollah (nicknamed Zaghi) and Fallah, and another person named Faraj Bazrkar, put Cinema Rex on fire. Finally, Takabalizadeh, along with 25 policemen and SAVAK officials and heads of provincial departments, were charged with the crime. Takabalizadeh introduced himself at the beginning: “I was addicted to heroin and cannabis. I was a welder. I was also selling drugs. I met Asghar Norouzi in our neighbourhood, and through him, I gradually found my way to the Qur’an study sessions.” The news, referring to his ideological affiliation with the Revolution, was published in Etela’aat Newspaper (September 27, 1980). He had not confessed after his arrest, and it is unclear why Hossein Takabalizadeh came clean on January 30. “My conscience is tormenting me, and I put the cinema on fire myself.” With this confession, he denies locking the doors of the cinema after the start of the fire, asking the court, “You need to pursue those who closed the doors of the cinema.” He had several nervous breakdowns during the trial, mainly when he spoke of the fire and his escape from the cinema and leaving his friends behind.

The book’s last perspective focuses on the Revolution, which is described through Takabalizadeh’s escape from Abadan, his subsequent arrest and imprisonment, and his release and going to the Alavi School, the first residence of Ayatollah Khomeini after his return from exile and one of the headquarters of the revolutionary forces in Tehran. Portraying the turmoil of the first months of the Revolution, the book describes how new ruling elites were reluctant to indict Takabalizadeh in the days when sin and crime were suspended, losing their meanings. He confessed in court that after the cinema was set on fire, he stayed in Abadan until the seventh-day ceremony of the martyrs was held and then went to Isfahan. He was arrested once but escaped from prison. He was arrested again on December 25, 1979. He was released from jail on February 12, with the Revolution’s victory: “I went to Isfahan. I came to Tehran a few days later. Imam Khomeini was residing at the Alavi School. So I went there to introduce myself. But it was crowded, and I could not, so I returned to Isfahan; I wanted to go to Abadan to turn myself in.” Confrontation of the victims’ families with the government officials trying to cover up and forget about this calamity marked these days. Newspaper excerpts indicate that the Abadani people demanded the interim Revolutionary government to punish the murderers of their children. Hence, the newspapers published a photo of him as a fugitive murderer. In his confession, Takabalizadeh said that every newspaper he opened, he saw his name as a SAVAK criminal: “In Abadan, I took refuge in the house of Mr Rashidian, a member of the first Islamic Consultative Assembly.” Rashidian, a witness at the trial, said he asked Takabalizadeh to hide in his mother’s house until he found a solution. Apparently, at this time, he relapsed into addiction and would talk about the burning of the cinema whenever he found a listening ear. At the same time, bereaved families arranged a sit-in in Qom as well as in front of the Abadan Tax Administration, calling on Mr Khomeini to punish the perpetrators of the arson. Takbaalizadeh, who gained more courage with the support of local officials, wrote a letter to Ayatollah Khomeini stating: “In the name of God, the Punisher of the Tyrants. I am Hossein Takabalizadeh, one of the devotees of Islam. Based on a calculated conspiracy, I have been wrongly accused of the Rex Cinema arson in Abadan, and my photo has been published in Javanan Magazine.” He further wanted the charges to be dropped. In response to the letter, Ayatollah Khomeini’s office asked Ayatollah Jami, his representative and Friday prayer leader of Abadan, to investigate the matter. The families of the survivors were demanding justice.

Takabalizadeh represented himself in court. The court sentenced thirteen to death, seven of whom were in absentia. In addition, seventeen were sentenced to prison. And five were acquitted. To this day, the revolutionaries still blame the agents of the previous regime for it. However, since Takabalizadeh’s accomplices either did not survive the incident or fled the scene, their responsibility in this regard is not clear. Those acquitted still remember September 6, when before they were called out one by one, and taken blindfolded from Karun Prison to the old SAVAK office to be handed over to the revolutionary forces. They were handcuffed for two hours in a dark room. Expecting to be shot, some were in tears. Others still hoped that the verdicts read in court might not be accurate. At that time, six death row inmates were transferred from the cell to the Abadan Cemetery. After reading the death sentence, they were shot in a cemetery’s corner. Their burial place in the cemetery was never identified. Two hours later, when the sun had risen, the door to the room opened, and the acquitted came out one by one to be transferred to the Karun Prison. Shortly afterwards, they were released.

Nikunazar narrates this historical event as a story. This form may help overcome censorship or help readers to reflect more on this heinous crime. Adopting this form, which distinguishes the book from official accounts and even the usual historiography of such events, does not seem to have undermined the author’s search for truth. The juxtaposition of the omitted narratives, along with the dominant ones and the author’s relentless search to unearth the hidden meanings and connections between the information buried under the official documents, make the book readable and place it as a historical work. But this is only the beginning. There are still many unanswered questions about the incident: in addition to the ambiguities about the number of victims, the details of the fire, and the fate of the other perpetrators, we still do not know how this tragedy has been discussed at decision-making levels in the government and local authorities over the years. We still need to reflect on the political and cultural meaning of accepting or rejecting different narratives. The burning of Cinema Rex is not just a humanitarian catastrophe; the seeds of the incident have penetrated the political, historical, and social space, creating a mystery that each group uses to condemn the other.

Nikunazar’s work does not offer a conclusive narrative. Historiography is about strengthening/changing a narration by presenting new records. Nikunazar’s work put a solid base for the historiography of this catastrophe by bringing together different sets of data, and by drawing results from books, documents left by SAVAK, the archives of two newspapers– Kayhan and Etela’at– and several documentary videos about the incident, most importantly, the existing videos on the 1980 trial. Thus, his work would inspire new research on the tragedy.

Comments are closed.